Introduction to community forestry

Institutional issues in community forestry

The emphasis on people and communities as the end users of trees is a hallmark of community forestry. This people-centred approach stands in marked contrast to the technical forestry approach that was typical of forestry operations in developing areas in the 1960s and early 1970s. The design of forestry projects has evolved significantly since that time. Most of the early projects focused on projected fuelwood and timber shortages and favoured the creation of vast timber plantations. The approach was generally highly technical and standardized, taking little account of existing production systems and agroforestry efforts. Local activities were often swept aside in order to make room for the plantations. Most of these early projects failed.

In the late 1970s international donors began sponsoring a second generation of forestry activities. The failures of the 'top-down' projects of the 1960s sent a strong signal that local participation was a critical element in forest management projects. In response, the next generation of projects 'downsized' the plantations, reconfiguring them as village woodlots and involving local populations in the implementation of the activities.

Villagers' roles were still largely limited to that of labouring in project activities, however. Villagers had little to do with the design of the projects or decisions about how they would be implemented. For their part, the project designers focused on getting the trees that they had identified as being the best for fuelwood (usually exotic species) planted and watered. Rarely did they pay attention to such issues as the multiple roles trees play in local production systems, or try to determine what trees were judged most useful by the local populations and why. Nor were the project designers much concerned with how the plantations would be used once they reached maturity or how the benefits would be distributed. If and when these issues were considered at all, it was generally assumed that local people would resolve any problems as they arose.

In retrospect, it is clear that despite the best intentions of these projects many failed at least in part because they underestimated the difficulties communities faced in resolving the governance and management issues associated with woodlots and other local forestry initiatives. Tree and land tenure issues plagued many of the projects and there were often conflicts over who had rights to the resources in the woodlots. In other cases, people were reluctant to invest labour in the woodlots if they were not sure that they would have access to their benefits. The cost of governance was also an issue in some communities. Communities that tried to govern their woodlots often faced substantial costs in both time and money as they sought to comply with official regulations. In some cases, people had to travel great distances to obtain permits to cut the trees they had planted or to get permission to process or sell the wood.

The field of community forestry came into being in the early 1980s as development organizations and rural development specialists began to absorb the lessons of the failed plantations and woodlots. They realized from their experiences that foresters could be more effective when they focused first on local communities' needs and then developed a collaborative programme with community members to improve the sustainable use of forest resources. Such programmes combined the knowledge and professional skills of the forester with the knowledge and resources of the local community.

Projects are now much more sensitive to the need to involve local people at all phases of project development and implementation, beginning with participatory planning exercises that identify local needs and adapt the project design to local circumstances. There is also a much greater understanding that social and economic issues are as important as technical ones in contributing to the success or failure of projects. Each issue requires painstaking attention at the project design stage and continuous monitoring while the project is being implemented.

|

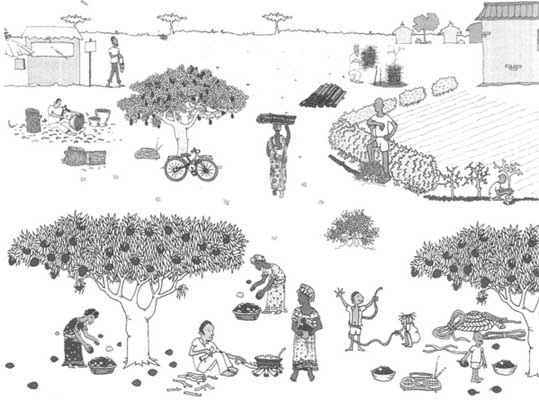

Community Forestry Activities Community forestry involves three kinds of activities. First, it includes peoples use of forest resources to meet their subsistence needs. This might involve hunting or gathering fuelwood, building poles, fruits, nuts and medicinal plants. Second, community forestry includes activities people undertake to preserve or improve their production systems. This might involve planting trees and bushes in hedgerows to serve as windbreaks or promoting the growth of trees in fields or pasture areas in order to fertilize the soil, protect against wind and water erosion, and provide forage and shade. Third, community forestry considers how people produce goods (based on forest resources) that will be sold or traded. This includes such diverse activities as producing tools and furniture, making rope and weaving mats harvesting timber, collecting wood and preparing certain foods and oils for the market. |

Among the social factors to be considered in the design and implementation of community forestry projects are institutional issues. From the earliest human communities, people throughout the world have had to decide who could use what resources, when, where and how. These rules, created by people to manage their resources, are defined here as institutional arrangements. Under this definition, national forestry agencies can be considered institutional arrangements as well as organizations. Local cooperatives that sell baskets made from palm fronds are organizations, but institutional arrangements as well. Land and tree tenure regulations and various procedures that communities develop to deal with conflict are clearly institutional arrangements.

People in all communities manipulate their rules. Institutional arrangements evolve over time. This happens because needs change or because people come into conflict or contact with other groups. As institutional arrangements change, people change their behaviour toward natural resources and this can often have an impact (which may be positive or negative) on the resource base. Evidence suggests, for example, that the species composition of even some of the most apparently wild Amazonian forests of South America is a result of human efforts over several centuries to improve the overall productivity of the resource base by planting and nurturing species known to produce desired products. It is fair to assume that the indigenous people of the Amazon region who engaged in these activities did not do so in a random fashion. Rather, they almost certainly had institutional arrangements, consisting of sets of rules, that defined tenure rights to the trees and their products or determined how and when those products could be harvested. Institutional arrangements for community forestry such as those of the prehistoric indigenous populations can still be found today, both among their present-day descendants and in groups as diverse as the Dogon in central Mali and the hill tribes of Nepal. Recent investigations document how, over the past several centuries, communities in West Africa have deliberately reforested areas to ensure their access to valued forest products (Fairhead & Leach, 1995). In short, wherever people make use of tree products, some institutional arrangements for community forestry are almost certainly in place. They may be more or less sophisticated and may have either a positive or a negative effect on the resource base, but they almost certainly exist.

|

Institutional Incentives Institutional incentives may be very straightforward and direct, with obvious implications for forest resources. A community may have a rule, for example, that people may collect only dead wood for fuel. If the rule is applied and sanctions are in place for those who do not follow the rule, then one would expect the tree cover to be denser there than in another community that has no such regulation. In other cases, however, the incentives are more complex and the impact may be less evident. A government regulation prohibiting the pruning or cutting of trees without permission from the authorities, for example, may be intended to protect forests and trees. But the effect may be just the opposite. Villagers may be concerned that even if they plant a tree in their own field they may not be able to obtain permission to prune it or cut it down at some later date. If they are concerned that the tree they plant might someday interfere with crop production, they may simply decide that under the circumstances it is better not to take the risk of planting a tree in their fields. The accumulated effect of all the villagers' decisions may be that there are considerably fewer trees in a community than there otherwise would be. In a case such as the one described above, the outsider may too quickly jump to the conclusion that "villagers do not understand the importance of trees" or "villagers are not interested in planting trees in their fields." In reality, however, villagers may be highly knowledgeable about the benefits of tree planting and protection. The problem is that they are discouraged from this activity by the institutional disincentives they face. |

Personnel working in community forestry and natural resource governance try to understand how institutional arrangements and changes in institutional arrangements affect people's interaction with their environment because of the consequences this interaction has for trees and forests. This is where institutional incentives are important. Rules create compelling incentives or motivations for certain types of behaviour. They discourage or negatively sanction other types of activity. Depending on the incentives and disincentives they face, people will perform actions that protect and nurture forest resources or they will carry out activities that are harmful to these resources.

In the past, project personnel have tended to avoid these institutional issues. In some cases this was because they simply did not recognize the importance of institutional issues for the success of the project. In other cases, they had a vague idea of why they might be important, but had difficulty understanding how to approach a subject that tends to be both complex and amorphous.

The purpose of this manual is to shed light on the importance of institutional issues and on how to approach them. Using examples from a hypothetical community forestry case study, it will show why it is so important to address these issues. It will also attempt to clarify governance issues, showing which factors are most critical and suggesting a systematic approach to gathering information about institutional concerns.

Careful analysis of institutional incentives and disincentives can help forestry project personnel and their government counterparts see beyond superficial and often misleading explanations of people's behaviour in order to understand some of the underlying reasons for the ways in which local populations interact with their environment. It can also help identify national projects, as well as local institutional incentives and disincentives to resource management practices. Once project personnel understand these issues, they will be in a better position to work with the local community to modify those institutions which appear to have undesirable consequences. Together, forestry professionals and local populations can see how local governance structures and rules systems might be strengthened so that forestry and other development efforts undertaken by the community will have a greater chance of success.

Before proceeding further, it should be noted that while institutional issues are critically important to the success of forestry activities, the process of institutional analysis and change is never simple and rarely easy. Governance, by definition, involves the use of power to make and enforce decisions. When decisions concerning access to and use of resources are being made, they invariably affect a large number of stakeholders who have different (and often conflicting) interests. The state may have interests different from those of local communities. Different groups within local communities may have divergent interests. In each case there will be interests that have more or less power to influence the decisions being made. Institutional analysis can help to clarify these different relations of force and how they affect the way resources are used. In some cases it may even help to empower those who have been left out of the debate as issues are explained and interests more clearly expressed. It would be naive to think that institutional analysis alone can change entrenched power relations within and between communities. But it can offer essential understanding of the chances any community forestry venture has of succeeding.

One of the implicit problems of institutional change is that in most cases powerful people not only have a strong influence when decisions are made but they also influence the rules about who makes decisions and how. And those rules often reinforce their positions of influence and protect their interests. Institutional analysis requires sensitivity to these issues, as well as persistence and creativity. In some cases efforts to change institutions as a result of such an analysis will be successful and the impact dramatic. More often the process will be a long one, results will be mixed, and the impact will come slowly as a result of incremental improvements over time. One result is almost certain, however: communities and outsiders who participate in a careful and systematic institutional analysis will emerge from the experience with a far more sophisticated understanding of the development process and the real constraints to implementing improved resource management strategies. An institutional analysis can also inform all of the groups involved of an activity's chances of success even before it gets under way, or of why an ongoing effort is not making progress. It can also clarify which national projects or local rules are influencing community forestry decisions and what options are available with or without institutional change.