Formal and non-formal rules

Working and non-working rules

The types of rules at work in the community

Implications for community forestry

Transactions costs

Gathering information about the rules system

Case Study: Analysis of the rules in Garin Dan Djibo

The two preceding chapters discussed how (1) the characteristics of the resource and (2) the characteristics of the community affect people's incentives to care for resources and to engage in collective action to manage tree and forest resources. Chapter 3 showed that some resources have characteristics that cause people to nurture and protect them because it is in their private interest to do so. Other resources with different characteristics do not offer the same incentives to careful private management. In fact if demand exceeds supply individuals will tend to overexploit these resources unless communities organize to regulate the use of the resource.

Since some resources require collective action to govern them sustain-ably, Chapter 4 addressed the characteristics of communities. In order to manage resources at the community level there is a need for a certain degree of social cohesion that permits people to work effectively together. Chapter 4 examined some of the factors that create incentives for a community to work together or that act conversely as disincentives to such collective activity.

Once a community decides to engage in a collective forestry activity to improve the governance of tree and forest resources, the next step is usually to create and/or enforce rules providing incentives for people to change their behaviour. This chapter, then, examines the incentives that are created by the rules that govern resource use.

Incentives created by rules are the easiest to understand intuitively. In daily life everyone faces incentives related to rules that create situations characterized by alternating reward and punishment: if one acts in a certain way one's neighbours, or the community or the government, will approve; if one acts in another way punishment will follow. But rules do not enforce themselves. Someone must monitor behaviour regulated by the rule and enforce sanctions in the case of non-compliance. This means that all rules do not create the same kinds of incentives. The incentive created by a rule that is enforced is different from the incentive created by one that is selectively enforced or one that is not enforced at all. The first type of rule, in which enforcement is predictable, will almost certainly lead people over time to comply with the rule. The second, in which enforcement is intermittent, may not discourage people from carrying out the illegal behaviour and may encourage them to attempt corruption if they are caught. The third, in which enforcement is non-existent, probably will not affect behaviour at all. In addition to the frequency of enforcement the severity of the sanction is a factor in determining how a rule affects behaviour. A rule that when violated can result in a person's expulsion from a community creates different incentives from one that results in nothing more than a token fine.

This chapter examines different kinds of rules, their characteristics and the incentives that they create for tree and forest management. In order to better understand how rules affect behaviour at the individual and community level it is useful to consider the different kinds of rules that exist. The first part of this chapter discusses the differences between formal and non-formal rules and between working and non-working rules. These distinctions are important, first in helping to identify all the rules that may exist in a given setting and then in understanding which rules actually have an impact on people's behaviour. This in turn may lead to the identification of non-working rules (whether formal or non-formal in origin) that need to be converted into working rules if trees and forest resources are to be governed effectively.

The second part of the chapter describes the hierarchy of rules that exists in any community. There are three types of rules that directly or indirectly affect people's behaviour:

· operational rules;

· collective decision-making rules; and

· constitutional rules.

Each of these types of rules affects a different type of decision. Operational rules are those that are intended to directly affect individuals' behaviours and the activities they undertake: what are people allowed to do, what are they required to do, and what are they prohibited from doing? These might be considered 'surface level' rules because they are closest to the behaviours that affect the resource base. At an intermediate level are collective decision-making rules. These determine how the operational rules are established: who gets to make the rules and how are the rules established and changed? Constitutional rules are the most fundamental rules in any political system. They determine who can participate in the political system, what the offices in the system are, how office holders are selected, and what powers and authority they can exercise. They also determine the procedures for establishing new units of governance and what needs to be clone in order to make and change collective decision-making rules.

Changing the rules involves costs in time, effort and money. Implementing and enforcing the rules puts further demands on the community. These costs are known as transactions costs. They have a major impact on the feasibility of implementing rule changes in community forestry. They are discussed in greater detail in the last part of this chapter before another episode in the case study shows how these concepts are applied in practice.

In analysing the rules at work in the community it is important to remember that rules may be either formal or non-formal. Formal rules comprise all the codified laws and regulations that are issued by a legislative process or formal decree. These may be promulgated at the national, local or village level but they are generally written down somewhere. Non-formal rules on the other hand are generally unwritten. They often derive from custom or practice. They are more likely to exist at the village level than at higher official levels but this is not always the case. For example, there may be a non-formal rule throughout a state that whenever the Governor passes through a village the inhabitants are expected to give him three sheep.

Whether a rule is formal or non-formal has little to do with the impact it has on people's behaviour. This will depend on many factors including whether the rules are enforced and whether people think the rules make sense and are fair. The effectiveness of the rules is captured by another distinction: the difference between working rules and non-working rules.

Rules are considered to be either working or non-working depending on whether they actually affect what people do. Working rules may or may not be written down and codified. In some cases they are in the form of local customs or practices that have never been written down; in other cases they may be formal government laws. The key is that to be considered, a working rule, the rule must actually affect the way people behave toward their resources. Working rules "are common knowledge and are monitored and enforced. Common knowledge implies that every participant knows the rules, and knows that others know the rules, and knows that they also know that the participant knows the rules" (Ostrom, 1990).

Working rules may have many different sources:

· traditional practices whose value has been verified by a community over time but which were never written down as 'rules';· agreements a community or communities have formally made among themselves, whether written or not;

· ethical or religious beliefs, whether written or not, if these give rise to rules that are monitored and sanctioned, e.g. rules governing attendance at prayers or other activities;

· written rules created by governments. (The working rules may be identical to these written rules, or may be 'adjusted' in light of local circumstances.)

As noted above, sometimes formal rules are working rules and sometimes they are not. It would be a grave error to assume that just because a rule is formal, it is applied and respected. Formal rules are considered to be working rules only when they have an influence on what people actually do. It is important to note that the actual influence of these rules on behaviour may or may not be what was intended when the rule was put into effect. Sometimes formal rules are irrelevant and are simply ignored in a particular situation. In other cases formal rules and non-formal rules are in conflict with one another: the working rule is the one that people follow in practice. This would be the case, for example, if a law prohibits cutting and pruning trees. Local people may feel that tree pruning is important. They may be willing to risk the consequences of contravening the national law, instead following local customs that dictate when and where trees may be pruned. In this case the local customs are the working rules because they are the ones that have an impact on actual behaviour.

The table below'' may be useful in understanding the difference between formal and non-formal and working and non-working rules.

In analysing the rules system in a community it is important to identify both formal and non-formal rules and then to determine which are the actual working rules in any situation. It cannot be assumed simply because a rule is a written one and is called a law or a regulation, that it does in fact influence how people behave. This can be determined only by talking to people, observing their practices and cross-checking information from numerous sources.

Table 2: Categories of rules

|

|

WORKING |

NON-WORKING |

|

FORMAL |

Codified Texts that Are Enforced |

Codified Texts that Are Not Enforced |

|

e.g. rule prohibiting commercial wood cutting on state lands without a permit |

e.g. rule providing that if an owner lends out his land for more than three years, the land reverts to state ownership |

|

|

NON-FORMAL |

Customs and Non-written Rules that Are Enforced |

Non-written Rules that Are Not Enforced |

|

e.g. customary rule concerning land loans prohibiting borrower from making permanent improvements |

e.g. custom of the ancestors (no longer in practice) providing that land borrowers give 10 percent of their produce to the owner |

Unfortunately it is often quite difficult to determine what the real working rules are in any given situation. When people are asked what rules determine their behaviour, they often list the formal rules (even if in practice they are non-working), especially when they think that the questioner is likely to 'approve' of that answer. Rather than asking directly about the rules, it is often more effective to begin by observing people's practices, going to the site where people use tree or forest resources to ask how and when various products are exploited. One can then proceed to inquire why practices are what they are and what rules govern people's decisions. In this way it is more likely that the researcher may discern rules that are associated with actual practices rather than rules that may not have any relevance to behaviour patterns.

Operational rules

Collective decision-making rules

Constitutional rules

People's behaviour is affected both directly and indirectly by different sorts of rules. A working rule against picking unripe mangoes, punishable by a fine, has a direct and immediate impact on whether an individual picks a fruit or not. Yet a national rule against the formation of Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) may indirectly also have a profound impact on people's management of resources, making it harder, for example, for a group of villages to organize to manage a community forest. This chapter now examines the three types of rules that influence the way people interact with then-tree and forest resources: (1) operational rules, (2) collective decision-making rules and (3) constitutional rules.

Operational rules are those that directly guide behaviour concerning any particular resource. First, operational rules define who can lawfully get access to the resource and what steps they must take to do so. Second, operational rules define how much individuals can harvest, when and where they may exploit the resource and what tools they are permitted to use. Third, operational rules specify who has to contribute money, labour or materials to protect and maintain resources in the community. Operational rules often change over time as people adapt to new conditions and needs in the community. The rules may also vary over the course of the year; rules governing access to fields under cultivation, for instance, frequently differ from those which apply after fields have been harvested.

Because operational rules have the most immediate and visible impact on people's behaviour, it is generally easier to begin by analysing the rules at this level. The study is likely to focus on rules that directly concern the resource that seems to be the most problematic. However, it is also useful to gather information about rules governing other resources since this can provide a basis for comparison and suggest other potential governance strategies.

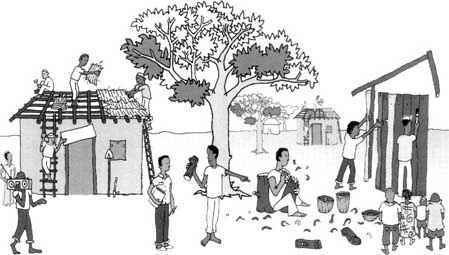

The easiest way to gather information about operational rules, as suggested above, is to go to the site where the resource is found and to begin observing and asking questions about how people are using the resource and what rules they have to follow. The first step is to identify evidence that a resource is being used. This might include observing people actually exploiting a certain tree product, either harvesting it or using it in an activity such as construction or cooking. Even if the activity cannot actually be observed there may be signs such as wood scarring or lopped-off branches that suggest that the tree has been exploited.

If there is evidence of use then someone has had access to the tree or forest resource. This does not yet reveal, however, whether any rules govern access and, if they do, which specific rule permitted the individual access or which rule may have been violated in order to obtain access. The next step, then, is to gather information about these rules. This involves finding out whether the resource is open access (no rules apply to either access or use) or controlled access, in which case one needs to find out the terms that regulate people's activities.

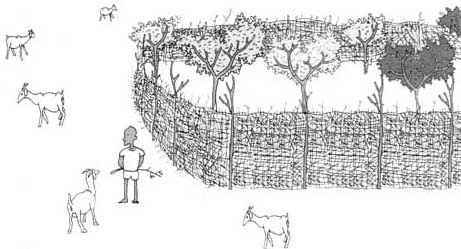

Careful observation can also provide clues as to whether there are efforts to control access to forest and tree products. These clues include fences, hedges or other devices that restrict free access; signs that animals are stabled, staked, fenced or tended by herders when they are on village lands; and evidence of the presence of guards from the village or some higher authority patrolling land in or around the village.

In addition to this careful observation, interviews with local people, leaders and officials can help to develop a systematic overview of rules concerning a specific resource. It is useful where possible to gather specific information on who can harvest what, when harvesting is permitted, how much can be harvested and what tools and techniques are permitted.

Operational rules in local communities are often highly complex. In many places property rights to valuable trees and bushes are not necessarily included in the property rights to the land those plants grow on.3 One person may own the land while another owns or has rights to tree resources found on that land. Operational rules concerning valuable tree and bush species can also vary with the location of the resource. Certain products can be harvested in bush areas without authorization while harvesting of the same products on a field may be controlled. The analysis of operational rules should attempt to capture this complexity because it is usually critical to decisions that people make concerning their behaviour toward resources.

3 For more information on resource tenure issues, see Bruce, 1990; and Fortmann et al., 1985.

The next type of rule is the collective decision-making rule. Collective decision-making rules can be described as the rules for making operational rules. Collective decision-making rules specify who can make, modify or revoke operational rules arid under what conditions. In most cases more than one person, group or agency will create operational rules relevant to a community forestry problem. While occasionally there are simple cases in which all the operational rules come from one source it is more likely that the local community will make some but not all rules. Others who may be involved in making the rules include NGOs and other donors who have financed projects, and government agencies working at various levels. Even within the local community there may be different jurisdictional levels such as hamlets or neighbourhoods within the larger village structure.

In analysing the collective decision-making rules, there are several questions to be asked.

· What group or individual is responsible for making decisions about a given tree resource?

· Who participates in making decisions by a given group?

· How are decisions made by that group?

Who makes decisions? Not all tree products will be subject to collective decision-making. In some cases, notably where trees are considered to be private property, individuals may have the liberty to make rules without reference to any higher collectivity. Even in these cases, however, certain rules and arrangements such as policing to protect private property rights may be the result of collective decisions. Tree resources that are not owned by individuals (open access or common property resources) will by definition be either not regulated or subject to collective control concerning access and/or use. Trees that produce public services, such as sacred groves considered homes for ancestors and other spirits, may likewise be subject to regulation.

There are likely to be several different groups that have responsibility for making operational rules about access to and use of tree products. Which groups have these powers may depend on factors such as the type or location of the tree or forest resource. For example, a committee of women may decide the rules about the harvesting of cooking wood while the male elders determine the opening and closing dates of the hunting season. Neighbourhood groups may decide the rules for exploiting common property tree groves within their particular jurisdiction. Some groups that are typically responsible for collective decisions about the management of tree and forest resources may include:

· the village leadership, e.g. the headman and his counselors;· a subcommittee designated by the village leadership;

· a neighbourhood committee;

· a kinship unit, e.g. clan or lineage;

· an age group;

· an ad hoc community or intercommunity committee established to deal with tree and forest resources in general or with a specific resource, e.g. a woodlot or windbreak committee, or a group that governs and regulates use of a larger wooded area;

· a religious leader;

· an association that regulates the behaviour of its members, e.g. local hunters, women fuelwood gatherers or commercial charcoal harvesters; or

· a national, subnational or local government agency.

Who participates in making collective decisions? It is important to identify not only the decision-making group, but also those of its members who have a right to speak and participate in making decisions. This will reveal something about whose interests are taken into account and may help identify those whose interests are neglected. It is useful to distinguish between those who participate as decision-makers (people who have a vote) and those who act as advisors (people who have no vote) in a given collective choice body. Who is included in and who is excluded from these decision-making bodies? Do they include people who represent all of the groups that make up the community: women? diverse ethnic groups? rich and poor people? people of all ages? newcomers? those who derive their livelihood from pastoralism, fishing, forestry, hunting and gathering as well as agriculture?

How are the rules made by the collective decision-making bodies?

Different groups have different ways of making decisions. Once again the mechanisms used to devise rules may vary with the situation. Rules may be decided:

· by a single person, e.g. a religious leader has the sole authority to open the harvesting season for nuts, berries, leaves, roots or bark;· by unanimity, e.g. all decision-makers must give their consent (each person has the power to veto the decision);

· by a simple majority, e.g. half the members of the group plus one member have the power to make a decision that is binding on all members of the group and even on outsiders when they are within the group's jurisdiction;

· by an extraordinary majority, e.g. a proportion greater than half plus one (for example, two-thirds) must concur for the decision to be valid;

· with the concurrence of multiple units, e.g. three decision-making groups from different villages are responsible for managing a common property forest and all must agree on any management decision; or

· with the concurrence of a government agency, e.g. decisions made locally must be approved by a representative of the forest service.

The third type of rule is the constitutional rule. Constitutional rules determine membership in a collective decision-making unit such as a community, age grade or lineage and whether and how such a unit can be created. They define the offices in the unit and the powers associated with them and determine how office holders are chosen. Constitutional rules also determine how collective decision-making rules can be created, changed and revoked. A decision to permit women to participate in the council of elders would be a constitutional decision. A decision to change from a system in which rules are decided by unanimity to one in which they are decided by a majority also would be a constitutional decision. In studying constitutional issues it is necessary to examine who has the power to make these kinds of decisions.

The following list describes some of the most relevant constitutional rules that may affect the management of tree and forest resources, and offers examples for each.

· Membership rules. These rules determine both who is eligible to belong to the group and who is eligible to assume leadership positions. Membership rules may depend on:- personal criteria such as gender, ethnicity, age and kinship;

- an event such as birth or initiation into an age grade;

- an action such as settling in a community or planting a certain number of trees; or

- a formal request to the unit's leadership.· Rules for creating new collective choice units. These rules determine who has the authority to create new collective choice units such as special purpose districts for tree and forest management or new general purpose local governments, as when a hamlet gains autonomy from the mother community.

· Rules for how collective decision-making rules are made and changed. These rules determine the process by which collective decisions are made and modified. As noted above, these rules define who decides whether decisions must be unanimous, whether some people will have veto power, etc.

Operational, collective decision-making and constitutional rules are found in all political systems. The national government has constitutional rules, collective decision-making rules and operational rules. These three types of rules may also be found at a county or district level, and they are usually found at the village and even subvillage level as well.

|

Three Types of Rules at Work in a Community Forestry Project If a village decides to devise a system to govern tree and forest resources on village lands, that system will undoubtedly take the form of a series of operational rules. An operational rule would determine, for example, how many days a month each family is required to provide labour for patrolling village lands in order to protect trees from marauding charcoal producers. The collective decision-making rule determines how this operational rule is made. In this case, for example, the collective decision-making rule may provide that operational rules are to be made jointly by the council of elders and the chief, and that all must agree (by unanimous decision) to make or change an operational rule. Perhaps some people in the community (for example, women) are dissatisfied with the way that decisions are made and want more voice in the process. They may wish to propose a change (In this case that two women serve on the council of elders). To make this rule change, they have to achieve a change in the constitutional rules since these are the rules that determine how collective decisions are made. In this community, the constitutional rules may specify that no change in the decision-making rules is valid unless both the village chief and the council of elders approve it and three-fourths of the heads of family thereafter also agree to the change. |

As described in Chapter 2 some resources are likely to be protected by individuals because they receive direct benefits from any investment they make in the resource It is relatively easy to promote sustainable management of these types of resources Sometimes it requires little more than changing the rules that prevent people from recouping the benefits of a resource in which they invest (for example, eliminating a rule that prohibits individuals from pruning the trees they plant on then own property).

However, because of their characteristics other resources are unlikely to be managed sustainably if it is left entirely up to individuals. Instead some broader community action is required. Chapter 3 discussed those characteristics of communities which determine their willingness to undertake this type of community effort and the factors that determine how likely they are to succeed.

Information gathered in the rules analysis proposed in this chapter will further highlight the potential for and constraints to collective action. Generally, the more superficial is the level of the intervention in the hierarchy of rules, the easier it will be to implement the activity. That is, it is usually easier to work within existing decision-making structures to implement a change in operational rules than it is to change the rules of collective decision-making.

The analysis of the rules should help to identify factors that are favourable to community forestry projects at each of the rules levels, and also those factors which are likely to cause problems. If, for example, there is one person who dominates the community rule-making system and that person is not trusted by large segments of the population, it may be difficult to change the rules in order to effectively address community forestry concerns. A critical factor in assessing rules systems is whether the various stakeholders who will be affected by community forestry activities have a voice in making the rules concerning these activities. If the interested parties do not have a voice in how rules are made and enforced, the result is unlikely to reflect their concerns. When people's concerns are not reflected in the rules the chances are greater that they will either ignore the changes or try to sabotage project activities. In such situations conflicts and even the eventual failure of the project are highly probable. This leads to the issue of transactions costs.

Transactions costs refer to the time, effort, material and financial costs involved in reaching a decision. This includes both the various costs of getting a rule established and accepted, and the costs of resolving conflicts that result from application of the rule. It is often easy to imagine changes in working rules that will make them better. Usually, because of the transactions costs involved, it is much more difficult actually to make the changes.

Examples of particular kinds of transactions costs involved in changing rules include:

· the time needed to come to a collective agreement within the community or other unit (clan, age grade, intervillage association) about which rules to change and how (the amount of time needed to come to such a decision may be quite sizeable, especially if some people expect to suffer from the rule changes);· the time and expense involved in obtaining approval for the changes if the local community lacks autonomous authority (as is usually the case) to make, modify and revoke rules in all areas affecting community forestry;

· the time and effort needed to implement the new rules once they are accepted within the community;

· the time and effort needed to monitor application of the rules and to ensure compliance; and

· the time and effort needed to resolve conflicts when disputes erupt concerning how new rules are enforced.

Transactions costs will be higher or lower depending, first, on how many different interests are affected by a given proposal to change a rule. Second, they will also depend on the constitutional rules and the nature of collective decision-making in the community. The more people who are involved and the more voices that are heard in the debate over the rule, the higher the transactions costs of making the decision are likely to be, as people who want to change a rule struggle to come to an agreement with those who want no change in the rule. In cases in which most people do not have a voice in changing the rules (when an autocratic chief makes most of the decisions, for example) the transactions costs involved in changing the rule may be quite low. This facility in changing the rules may, however, involve much higher transactions costs at later stages. The costs of monitoring and the costs of resolving disputes will almost certainly be high if people feel that decisions were made against their interests and without their input.

Because of the complexity of rules systems it is useful to gather information from numerous sources. This information can then be cross-checked and supplemented as more information becomes available. Local people are likely to be the prime source of information since no one knows better than they do how local decisions are made and whether formal national rules are or are not applied locally. They can best describe the real configuration of working rules from all sources that affects behaviour within the local arena. It is often useful to start with an exercise such as a Venn Diagram (a tool used in RRA and PRA; see Appendix 1) to gain an overall picture of a given community's social structure. This kind of diagram helps to highlight organizations, committees and leadership. With this as a starting point, discussions around the diagram or independently with groups and individuals can explore some of the issues raised in this chapter. It is often most useful to discuss actual cases in which the community made a decision about tree and forest use or in which an outside authority applied an official rule in dealing with a local infraction. This will help to identify the working rules.

In addition to local sources of information there are likely to be other people who have experience with decision-making in the community or with decisions made at other levels that may have an impact on the community. They might include foresters and agricultural extension workers. A lawyer who has actually been to the field, worked with people on forestry problems and perhaps helped them draft bylaws for an association might be an ideal source. Local consultants and other individuals who know the issues and have practical experience in the sector also can be extremely helpful. These people may also have knowledge about the political and legal feasibility of the type of project being considered or a rules change that has been proposed.

Chapter 5 has provided a detailed framework for analysing how rules affect behaviour. Rules occur at three distinct levels: operational, collective decision-making and constitutional. At each of these levels rules can be divided into those which are codified and usually written down (formal rules) and those which are the product of custom or practice. Rarely written down, the latter are sometimes known as informal rules. Rules can also be divided according to a second characteristic according to whether they are working or non-working rules. Working rules are those that affect human behaviour because they are enforced. When people think about an activity or plan their strategies they take working rules into account. Working rules may be either formal or informal. The job of persons studying institutional issues in community forestry is to understand the array of working rules, at all levels, that may have an impact on the project they are trying to undertake. How a rule works in a specific situation depends on how it interacts with other rules that apply in the same situation. If, for instance, a national rule conflicts with a community working rule but the former is enforced only occasionally, then the local working rule may be overridden in those infrequent cases but may apply the rest of the time.

In addition to studying the rules that are already in place, the community will want to consider changes in the local and external rules systems that will be necessary to make the new activities successful. Such an analysis would start with whether the rules for the governance and management of a given renewable resource are really needed in light of the characteristics of the resource as discussed in Chapter 3. If people's private incentives are sufficient to ensure good management of resources it may not be necessary to put any new rules into place. However, if the analysis of the resources suggests that private incentives are insufficient to guarantee good management, then the field worker will want to work with the community in further studying the implications of changing the rules systems. First of all, does the community, as described in Chapter 4, have the interest and cohesion needed to engage in a governance activity such as revising resource management rules? Second, what type of rules changes will be needed? At what level will rules be changed? What will be the transactions costs of such changes in the rules systems?

The Guidelines Box on the following page addresses the practicalities of researching rules in an institutional analysis. Then the case study follows the Garin Dan Djibo team as it goes on to analyse the rules structure governing resource management in the community and tries to determine what this implies for the management of gawo trees on village lands.

|

Guidelines for Implementing an Institutional Analysis: The purpose of this part of the study is to understand how the rules at various levels create incentives or disincentives for how various stakeholders behave concerning resources. 1. Begin by identifying the various operational rules governing the use of the resource in question. Also identify the rules governing other natural resources in the community. Note the source of the rule: is it a formal or non-formal rule? 2. Evaluate the extent to which the rules identified are working or non-working. Are the rules enforced? What are the sanctions for transgression? Are the sanctions applied? Under what circumstances and by whom? The best way to get information about operational rules and especially about working operational rules is to go to the site where people use the resource and to interview various users/owners about what rules apply under different circumstances. For any given resource, this may involve several interviews since different users and people who perceive themselves as controlling the resources may have different perspectives on what the rules are. It will also be useful to interview government officials and project personnel who work with the resource in question. To make sense of the information ^collected, it may help to organize it into a table. 3. Identity rules at the collective decision-making and constitutional levels that affect governance of resources in the community. The Venn Diagram (see Appendix 1) is a useful tool for exploring the 'rules for making rules.' The Venn Diagram can be used to indicate in a clear, visual fashion the various individuals and groups in the community arid outside that have decision-making powers over resources or influence over their use. Once these individuals and groups are identified the follow-up interview can be used to explore the kinds of authority wielded by various groups or individuals, how they make decisions (who is consulted; who actually participates in the decision; whether they vote, reach consensus or follow the directives of one individual; etc.), what the basis of the group or individual's authority is, and so on. This inquiry can be completed by individual interviews with the various groups or individuals to understand better how they make decisions and to determine the limits and extent of their authority. It may also be necessary to consult higher authorities for a better understanding of the extent to which local communities are permitted jurisdiction over the governance of resources and under what circumstances. 4. In light of the information collected in the various activities described above, determine what incentives the rules create for peoples use of resources and their capacity to organize collectively to govern the use of resources. Which rules promote sustainable use and which discourage it? Which encourage collective action and which discourage it? 5. Having determined the type of rule that is causing problems, the origin of the rule, whether it is formal or non-formal, etc., consider what would be required to change any rules that have been identified as being problematic. |

Table 3: Operational rules governing resource (name of resource or output)

|

Rule |

Source of Rule |

Working/Non-working? |

Sanction/Other Observations |

|

In this column make note o each rule that is identified |

In this column describe the source of the rule Note whether it is formal or non-formal and at what level the rule was made Was it made by an individual in the community? Is it a village rule? Did some higher government authority make the rule? |

In this column evaluate whether the rule is working or non-working If it is a working rule in some cases and a non-working rule in others, describe the circumstances in each case (e.g commercial woodcutters may obey government edicts but local cutters do not) |

In this column note the sanctions that are applied to those who transgress the rule Differentiate between the sane lions that exist only in theory and those that are applied in practice Indicate who applies the sanction and how |

|

As they continued their study of the gawo issue, the Garin Dan Djibo team focused on all the rules it could think of that might affect people's decisions about how they cared for and used the trees in the village. The team also explored decisions made by the herders and the rules that they followed in making resource management decisions. As the study progressed the team identified some key ambiguities that were at least in part responsible for the fiasco that Maman had experienced in his field. Identifying the Operational Rules Team members identified two important operational rules concerning how trees on private fields could be used. The first rule concerned trees that grew naturally on fields around the village. It was a rule that had been passed down since the time of the ancestors. No one could remember that it had ever been specifically debated but all knew that it was the 'rule of the land' on village territory. The rule, though never written, was well understood by all: fields and the trees that grew on them were closed to outsiders during the rainy season and whenever crops were present on the field. During that period access was limited to the owner and to those people who received specific permission from the owner to enter the field or use some tree product that grew there. Once the crops were harvested, however, the land became open access for purposes of grazing. During the dry season anybody could harvest products from the trees on the field as long as they did not seek commercial gain from the product (in which case they would need permission from the owner) and as long as they did not do any permanent damage to the tree. A second rule was of more recent origin, instituted some 1 5 years earlier when mangoes were first introduced into the area. It explicitly regulated activities concerning trees that were planted on fields. Previously there had been no planting of trees in fields and so there had been no need for such a rule. But when the first mango seedlings were brought in by the extension agent, the village had identified a need to provide security for the investment that farmers made in watering and protecting these trees. Most were planted in compounds but some farmers had taken the trouble to plant trees in their far fields as well. A rule was adopted that no one could exploit the product of any planted tree (regardless of the season) without first obtaining permission from the owner. After careful discussion the team members all agreed that Maman's gawos fell into this category. They were not exactly 'planted' but Maman had carefully protected the seedlings and invested effort in the activity much as he would have done had he actually planted the trees. Until the issue of Maman's gawo trees arose, these two rules, both of them informal but working, had satisfactorily governed the use of tree resources. There were only very occasional conflicts when, for example, a farmer argued that the trimming of a tree for fuelwood had permanently damaged a tree, and he sought compensation from the cutter (who usually denied that the damage was permanent). The team members noted that another rule existed as well, but all agreed that in practice this was a non-working rule. A formal government edict decreed that no one had the right to cut trees at any time for any purpose without getting permission from a forestry agent. While the villagers were at first hesitant to say so in front of their local agent it became clear from the discussion that this rule was universally ignored, except in the woodlot, which had been established with help from the state. In that particular case, in order to avoid coming into possible conflict with the state, the villagers had simply decided not to cut the trees. (This was the problem to which the chief had alluded in the very first meeting with the forester and extension agent.) Perspective of the Herders Then the three team members who had spent time with the herders reminded the group of the information they had collected. The herders, they reported, could without difficulty recite the rules concerning tree use in Garin Dan Djibo. They considered their mutual relationship with the villagers to be important and wanted to avoid conflicts as much as possible. They were quick to point out that aside from the occasional mango their children might pick up while moving through the territory, they never picked fruit from trees in the fields and certainly would not consider selling anything they got from village lands. At the same time, however, they readily admitted that they cut leaves and branches from trees when the grasses were too poor to support their herds. "How else," they had asked the Garin cultivators, "could we keep the animals we herd for your village healthy during the late dry season?" They noted that this practice had been in existence since the time of their forefathers.

When the issue of Maman's trees was raised, none of the herders was prepared to take responsibility for cutting the branches. They admitted that from what they had heard the responsible person had probably been a bit more enthusiastic in his cutting than he should have been, but they also remarked that other gawo trees would eventually grow back. And furthermore, they noted, since gawos are naturally growing trees given by Allah, it was not for Maman or anyone else to tell them that they could not harvest what they needed to live and serve God. The team members concluded from this discussion that there was a problem with how the operational rules were being interpreted, and more precisely how the term 'planted' was being defined by different resource users. This was noted as an issue to be explored further. Most thought that stronger rules were needed to protect any trees in which the owner invested a significant amount of effort or money. In the meantime the group turned its attention to identifying relevant collective decision-making rules that might affect the community's ability to manage resources. Collective Decision-making and Constitutional Rules in Garin Dan Djibo The team's analysis of the collective decision-making rules suggested that the community was in a state of transition. In the past virtually all decisions concerning resource management had been made at the community level, usually by the Council of Elders. These were then presented at a community meeting where details were worked out and a consensus was reached on how the rules should be applied and enforced. Since the time of the new chief, however, community meetings were almost never held and when they occurred they usually provoked rancorous discussion and were unable to reach any consensus. As a result neighbourhood leaders were taking more initiative to promote decision-making at their level and to avoid situations in which the whole community needed to get involved. While recognizing this reality, the team members were concerned that it was not entirely satisfactory for good resource governance. They noted in particular that a decision to change the rules about outsiders' use of trees on fields would really have to be a community-wide decision. Each neighbourhood could not expect to make its own decision and have outsiders respect it. There were, however, other types of decisions that could best be made or implemented at the neighbourhood level. The team concluded from this that there was a need to strengthen decision-making structures at the village level if forestry resources were to be governed effectively while leaving room for the neighbourhoods to make decisions that they could effectively implement and enforce. Finally the team considered whether there were any constitutional issues involved in the gawo case. In the first discussions there did not seem to be anything that concerned the constitutional level. The team members were just about to move on to their final analysis when the forester reminded them of one of the comments made by the herders they had visited: "Those trees were planted by God and belong to God; no one can tell us that we cannot use those branches when our animals are hungry." The villagers, for their part, were equally convinced that since the trees were on their territory they had the right to change the rules governing their management and could control the actions of anyone coming onto their lands. In short there seemed to be a fundamental difference of opinion about who was covered by decisions made by the village. While the herders were quite willing to follow village directives concerning the use of most resources, when naturally growing trees were at stake the herders had different views of who had rights to make the rules. The team members did not agree with the herders' perceptions. In fact they became quite vocal in expressing their annoyance as they discussed what they perceived to be ridiculous assertions by their pastoralist neighbours. At the same time, however, they were forced to acknowledge that any solution to the problem would have to address this issue. The herders would have no incentive to follow a rule if they did not accept the legitimacy of the rule-making body in that particular domain. As Maman reported the day's proceedings to his friends at the mosque before prayers that evening, they all had a good laugh that his small efforts to tie red scraps of cloth around his gawo trees had brought up all these important issues. "Maman," they teased him, "you're starting to talk like a president with all this gibberish about rules and constitutions. Don't you forget that you're just a wizened old peanut farmer like the rest of us!"

|