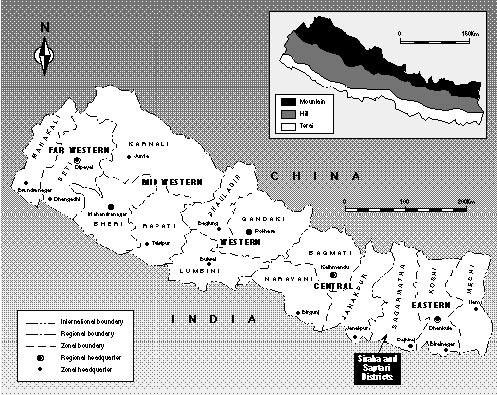

Map 1: Nepal Development Regions and Zones

Tree and Land Tenure in the Eastern Terai, Nepal: A Case Study from the Siraha and Saptari Districts, Nepal

by Bhishma P. Subedi, Chintamani L. Das and Donald A.Messerschmidt

Edited by Daniel Shallon

In January 1990, the Institute of Forestry (IOF) in Nepal was approached by the "Development of Income and Employment through Community Forestry Project" (DIECF) to conduct a study of tree and land tenure, using rapid appraisal methodology, in two villages in Nepal's eastern Terai (lowlands). The Swedish International Development Authority (SIDA) through the Forests, Trees and People Programme of the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) was requested to fund this study and provide backstopping. The DIECF project, jointly managed by Nepal's Department of Forests (DOF) and FAO, had its offices in the town of Lahan in Siraha District.

Fieldwork was begun in spring 1990, though this was a difficult time for Nepal. A popular uprising against the government was fomenting, and the study was interrupted by nationwide civil unrest. During early April, travel on the only road to the eastern Terai was considered unsafe. The political sensitivity that surrounds land tenure issues also caused problems, and the research team's presence in the districts came under suspicion by civil authorities, politicians and some villagers. For many weeks during the study period, the entire university system was closed, including the campuses of the Institute of Forestry. When conditions improved, the fieldwork was completed and workshops were held to discuss the findings and the methodology. The problems encountered in the field, a lack of baseline information and the wealth of data collected, however, slowed completion of the work. In that sense, it was not as "rapid" an appraisal as was first envisioned.

The report has five parts. This chapter provides the necessary background to the DIECF Project, discusses practical and theoretical issues of tree and land tenure and provides an overview of the research topic and methodology. Chapter 2: SETTING describes the districts and the two study villages. In Chapter 3: FINDINGS the data are presented, with detailed discussion and description of land and tree resources and their use. Chapter 4: CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS covers certain conceptual issues and suggest ways to deal with scarcity, equity and policy.

The objective of Nepal's DIECF Project is to increase benefits of forest and tree resources to rural communities, especially to the poor, who are nutritionally vulnerable. It is also designed to promote ecologically sound and economically sustainable management of degraded and potentially sensitive forested areas of the two districts.

The DIECF became operational in 1988. Several external factors disrupted and slowed project implementation between 1988 and 1990. Originally, it was intended for the mid-Himalayan hills where substantial community forestry experience already existed. The government decided, however, that Terai communities could benefit more from the effort. This meant, however, that the project started in a virtual vacuum, without basic socio-economic, ethnographic and other data and information on the project area.

In addition, the project period has been an economically and politically difficult time for Nepal. In 1989, due to a trade dispute with neighbouring India, no fuel was available in the county from March to December, making all project activities requiring transport almost impossible. Then, within a few months, life in Nepal was further interrupted by a popular revolution that brought the country, the project and the research to a standstill, particularly during March-April, 1990.

An important role for the DIECF is to generate a database regarding community forestry in the Terai. Several studies were planned, including a nutrition baseline study, a socio-economic baseline survey and research on potential products and markets for tree and forest products. Because of the short time involved, and the interruptions, these studies have had to be conducted simultaneously. The tree and land study, therefore, was not able to fully utilize the results of a baseline nutrition study until the writing phase, and a planned socio-economic baseline study has yet to be completed.

One focus of the research in Siraha and Saptari was to determine to what extent it is possible to adapt the methodological guidelines prepared by J.W. Bruce in his Rapid Appraisal of Tree and Land Tenure (Bruce 1989), to circumstances in the Terai for regular use in monitoring and evaluating these community forestry activities.

In early 1990, Nepal's Ministry of Forests, Community Forestry Development Division (CFDD) published its Operational Guidelines for Community Forestry (Nepal 1990), based in large part on the mandate of the Forestry Sector Master Plan (Nepal 1989). The operational guidelines describe the process which leads to community forestry through identifying and supporting user groups and the transfer of managerial responsibility over local forests, from the government to the local people. A main feature of this process is the collection of information by district forestry rangers and officers for purposes of planning and monitoring community involvement and giving appropriate technical assistance for local success. This includes information on traditional and local forest use and potentials, local priorities and so forth. Consequently, the development of methodologies for accomplishing this task has become an important goal.

Because of the critical role that district forest officers and rangers must play in the development of community forestry, it was important that they be involved in the tree and land tenure study. But, as the study was severely disrupted, their participation was not possible to the extent intended. Nonetheless, some of the fieldwork was conducted by rangers from the district forest and project offices. Through this exercise it became clear that whereas the rangers gained important new interpersonal skills for working with villagers, their short and incomplete training by the research team did not really equip them with sufficient confidence in rapid appraisal as a methodology. Further development of the methodology and more training for field staff is necessary if rapid appraisal is to be given serious attention as a legitimate research tool for information-gathering in support of community forestry.

A particular challenge for the DIECF Project has been the lack of written information on the Terai in general and on the two districts, Siraha and Saptari, in particular. This applies specifically to information on social, cultural and economic activities and on the communities' resource base. This dearth of information has led to a situation where planning for community forestry has been largely based on unproved assumptions about the relationship of local people to forest and tree resources.

Community forestry policy in Nepal is largely based on experience gained in the hill areas. There is a feeling in Nepal that the Terai experience is unique, based on the area's large size and complexity. Among its problems are: forest product smuggling across the international border with India, demographic pressures leading to large-scale encroachment on government reserve forest lands and the consequent damage to soils and related resources that encroachment exacerbates. In some instances, cross-border smuggling is so large a problem that it degenerates into virtual warfare between the forestry authorities and smugglers. Similarly, because landlessness is so critical and population pressure so severe, illegal encroachment has become a highly political issue. It sometimes involves unscrupulous politicians who encourage desperate people to become squatters with the promise that, once elected, their illegal claims will be registered and legalized. And, because squatters often encroach on marginal lands, land degradation and soil erosion pose a continual threat to the basic integrity of landed resources.

These sorts of problems are of such a degree and dimension in the Terai that they are often considered unique to the lowlands. It is also thought that they are not fully appreciated by policy and programme planners more familiar with the relatively more resource-rich circumstances in the hills. Coupled with these is the fact that community forestry activities in the Terai have been particularly difficult to initiate and stimulate. Some observers point out that in the Terai, the sense of "community" so commonly expressed in the hills does not exist, or is greatly reduced. This may be because of the lack of historical homogeneity of Terai communities compared with those of the hills. The Terai's demographic and caste/ethnic heterogeneity, deriving largely from its settlement history and patterns, are all thought to be disruptive factors in any attempt to create a sense of community and common purpose. A principal factor in this situation is the mass migration and settlement that has occurred since the 1950s (dating to a malaria eradication programme begun at that time) and because of the high feeling of communalism that exists among the migrant castes and ethnic groups settling there.1

These concerns have led, furthermore, to a reassessment of the notion of "user group" in the Terai context. The "user group" is the fundamental element of community forestry design and development in Nepal. It is usually defined in geographical terms as a group of people - community, ward, neighbourhood, hamlet - claiming traditional use rights to specified forests and products of forests in the immediate vicinity of habitation. In the hills, such groups and the larger communities in which they exist are easily recognizable entities defined on the basis of geography, culture, economy, demography and political factors, existing within easily distinguishable watersheds or valleys.

Terai communities and groups, however, are not so easily recognized. There, in place of geographical discreteness, other demographic and sociological factors (caste, ethnicity, length of residence) dominate. This leads to a re-examination of the basis of community forestry design for the Terai, and the whole foundation for acting on the basis of "community" at all. It may be, for example, that tree and forest users in the Terai are better defined in terms of the resource or forest product used, or on dominant occupational identities on which so much of Terai life, and Hindu caste life generally, is defined. Or, perhaps, on the basis of these considerations combined with an understanding of what social groups have the vital cultural knowledge about specific resources or resource systems.

The situation in the Terai is further complicated by the severity of landlessness and treelessness among certain populations. Some groups of people currently have no direct or legal access to forest and tree produce, and have not had access for generations. The vast bulk of the remaining forest resources in the eastern Terai is found north of the east-west Mahendra Highway. Populations north of the road have relatively easy (but illegal) access. For villagers living south of the highway access is extremely difficult. These and other geo-demographic variables need particularly close scrutiny.

In order to begin to develop a community forestry strategy that meets the specific needs of the Terai, one that "makes sense" under Terai conditions for Terai dwellers, it is necessary to ask questions specific to the Terai for information that has been heretofore unknown and unconsidered in the hills of Nepal. On a very narrow base of information, this study has had to begin to understand the nature of the most fundamental and elementary relationships between Terai communities and their tree, forest and other landed resources. The tree and land tenure study helps fill certain gaps in knowledge. It provides a beginning in the creation of an information base on which to design policy and improve local development programmes and, ultimately, to enhance the resources of the land and the lives of both the landed and the landless and treeless people of the Terai.

Bruce defines tree and land tenure as a "bundle of rights" (1989:1) concerned with ownership, tenancy, usufruct, access, acquisition, partition, labour, extraction of products and benefits. Tenurial rights may belong to an individual, household or family, neighbourhood group, community, public body or some other defined social entity. In Nepal, issues of tree and land tenure typically include the rights of communal groups (castes and ethnic groups), whose traditional tenurial practices and conflicts are of great concern. Extreme sensitivity often accompanies issues of tenure over natural resources. This sensitivity reflects their real or perceived scarcity and generally high value, and a propensity of governments to over-regulate them without a corresponding capacity to manage them.

The objects of tenure - land, trees, forests and water, and their products - are defined by Bruce in terms of three categories: private holdings, commons and forest reserve. In the study area, Bruce's categories are slightly expanded in perception and practice to include water (ponds and pond-side trees on private land or commons) and unforested reserve lands (such as lands reserved for government buildings or installations).

The study of tenure is further concerned with distinctions between customary practice and the rule of law. The distinction between custom and law is augmented and sometimes confused in Nepal, and in other societies, with the related issues of regulated (niyamit) versus unregulated (aniyamit) tenures. Prohibitions on the use of a particular resource may be thoroughly spelled out in law, and yet, for many reasons, remain unregulated in practice. This mis-match between law and actual regulation can be due to overreach on the part of a government unable or ill-prepared to police its resources. Or it may be due to a benign attitude on the part of authorities towards use of a prohibited resource by vulnerable populations such as the very poor, or by powerful social groups or political factions. Law must not be equated with regulation, or custom with lack of regulation, as this study has shown.

Sometimes trees are thought to be a part of the land on which they grow. They are often assumed to be fixed property, like buildings, owned by whomever holds title to the land. But in fact, trees are an inherently separable form of property, like water or livestock, and rights to them can accrue quite distinctly from the land on which they are located. Rights are also sometimes attached to parts or products of trees - such as blossoms, fruits, branches, leaves, roots and even tree shade, which in the heat of the Terai is often perceived as a public benefit, a free good, particularly of trees on commons (along paths and roadways, for example). In other words, rights often transcend the issues of who owns the land beneath or alongside a tree, forest or pond, or who owns the tree, the forest or the pond itself. Rights of ownership and particularly of access to all or part of a tenurable object may be quite distinct from the ownership of the object itself or the land on which it stands.

Precise knowledge of tenure is of great importance to natural resource development policy and to projects, particularly those dealing with landed resources. It is mandatory to understand tenure in instances of severe landlessness and treelessness, such as found in the Terai. Yet, tenure issues are all too often misunderstood or neglected. Many questions must be raised, and their answers must be well understood before development planning is complete and implementation ready to begin. Developers must be prepared to reconsider their assumptions in mid-course, as new or improved understanding arises.2 Planners and implementers should be asking pertinent questions about tenure from the start, questions like: Who has rights in the land, the trees and the water? Have those rights changed over time? Who has access and control? When and for what purpose? How is tenure defined by custom and by law? What is public and what is private? How are rights allocated, exchanged or transferred? How are they likely to be affected by development? The potential list of questions is very long. More important, perhaps, are questions that ask: what makes sense when tenure in land, trees, forests and other landed resources are under consideration for project development? These questions are difficult to frame, and often much more difficult to answer quickly and with certainty. Because of the sensitivity of tenure issues, clear understanding does not come easily and typically not on first asking. Prolonged and in-depth fieldwork and observation may be necessary, which may render rapid appraisal inappropriate for some issues of tenure.

Such research is relatively new in natural resource development, and the more that is learned about local tenurial customs the more often they seem to diverge from government and donor policy and development objectives, and they are frequently ignored. This is a grave mistake, and more than one project has encountered problems in the face of complex tenure issues. This study has been designed to help in understanding them in the eastern Nepal Terai.

This study is a preliminary foray into tree and land tenure in two selected villages. The preliminary aspect of the study should be underlined, for it is only a beginning and raises far more questions than it answers. Using ethnographic, forestry and other research techniques adapted to the rapid appraisal methodology, it addresses the nature and the normal functions of tenure and to some extent their origins.

The study is particularly concerned with the relationship between tenure in trees, the planting of trees and the nature of tree/forest husbandry. It deals with questions of tenurial equity and sustainable resource management, utilization and conservation. It was designed to assist in making national resource management policies that make sense in the villages, to the people on the land, both those with land and trees and those without.3

The goals of the study were therefore to:

Three conceptual issues guided the inquiry:

This type of study is relatively new to forestry and development, generally, and to forestry in Nepal in particular. It is hoped that the data and analysis from this work will provide a foundation for improving community forestry activities in Nepal and for identifying important future research needs.

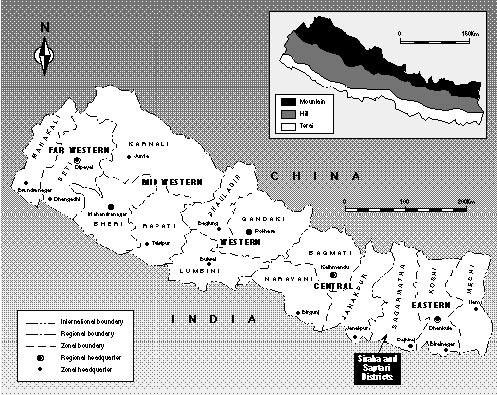

The study of tree and land tenure in the eastern Terai was conducted in two village communities, one each in Siraha and Saptari Districts, Sagarmatha Zone, Eastern Development Region. Siraha and Saptari are very much alike in many ways; important similarities and the few differences are noted in this chapter.

Physical Description. Siraha is the smaller of the two districts in size, with a total area of 1 023 sq km (Maps 1 and 2). The district is divided geographically into two distinct parts. The north is dominated by the Churia (or Siwalik) Hills (227.2 sq km, 28.5% of the total district area). The Churia Hills are of unstable sandstone and conglomerates of great geological antiquity. The area immediately at the foot of the Churia Hills is called the bhabar. It is characterised by porous soils, with boulders and gravel and a low water table. Although large areas have been recently cleared for farming by immigrants from the hills, agricultural crops do not do well in the bhabar.

The southern portion of Siraha lies on the flat Terai plain (705.8 sq km, or 71.5% of the total district area), bordering in the south on the Indian state of Bihar. The Terai is an extension of the northern Gangetic plain. It was formerly a dense forested belt but, following an anti-malaria programme in the 1950s, it was opened to clearing and farming, and now very little of the natural forest remains. The eastern Terai is nearly level, except for hilly portions at the base of the Churia Hills; it is recent alluvial and the soils are loamy and deep. The altitude varies across the district from 895 m to 75 m, north to south, over a distance of 28.8 km.

Five rivers flow out onto the plain from the Churia Hills: the Kamla, Mainabati, Gagan, Khutti and Balan. All these rivers flood heavily during the monsoon, and with the exception of the Balan and Kamala, all go dry during the winter season. The district has a subtropical climate and is heavily influenced by the monsoon (June-September) with an average annual rainfall of 1 442 mm. The maximum temperature averages 36º C and the minimum 17º C.

Map 1: Nepal Development Regions and Zones

Demography. According to available statistics, district population is 411 336 (54% male, 46% female), which breaks down into 74 788 households with an average household size of 5.5. Population density is 346 per sq km. Demographic trends in Siraha and especially Saptari are heavily influenced by migration from the hills and from India. Siraha has 111 communities (formerly village panchayats), plus the municipality of Lahan (formally town panchayat). Literacy is estimated at 12% overall, with no more than 6-7% for women (Vaidya 1990:3). There is a lack of reliable economic, statistical and ethnographic data on either district (see Appendix B, Table 8: Siraha and Saptari Districts Compared).

Siraha residents live in mixed ethnic and caste communities. The major groups are Yadav, Chaudhary (Tharu), Jha, Mishra, Brahmin and Chhetri, followed by Tamang, Rai, Newar and Magar. The latter groups, plus many of Bahun and Chhetri, are recent migrants from the mid-Himalayan hills. A majority of the population speaks Maithili, a language closely related to Hindi. Nepali is the second most commonly spoken language. Most men and some women are bilingual. Some minority ethnic dialects are also spoken, such as Tharu.

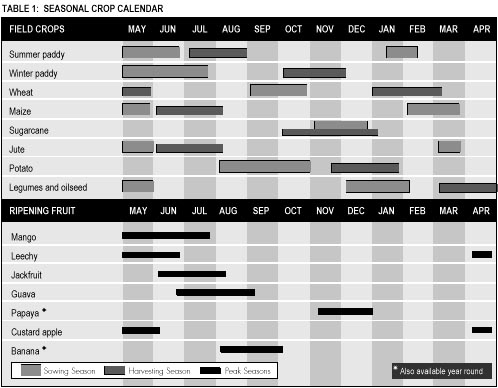

Economy. The residents are primarily farmers raising a variety of subsistence and cash crops. Types of crops cultivated are grains (paddy rice, wheat, maize), legumes and pulses, oil seeds, vegetables, fruits (mango, leechy, papaya, guava, jackfruit and custard apple) and some cash crops (tobacco, sugarcane). Agricultural crops from these and other districts of the Terai are important to all of Nepal, to the point where the Terai is sometimes called the "granary of Nepal". Livestock includes cattle, water buffalo, goats and some pigs. Local small industries are mostly agriculture-related, and include grain mills, oil seed presses and brick factories.

Map 2: Siraha and Saptari Districts in the Eastern Development Region of Nepal

Paddy rice (Oryza sativa) is the main field crop of both Siraha and Saptari. Where there is irrigation, or where pumps are employed for watering fields, two crops of paddy are grown on the same fields, summer and winter. The variety of paddy differs by the season; summer paddy includes local varieties called auns (Maithili), gaddair (Maithili) and gamhari (Maithili), and winter paddy is called agahani (Maithili). Wheat (Triticum aestivum) is the second most important cereal crop in this region. Unlike paddy, it grows best in well drained fields. Wheat has been grown here in small quantities for a very long time. It has gained in popularity only since the 1970s, following the "green revolution" and the introduction of hybrids and new techniques. Maize (Zea mays) is grown mostly in the bhabar soils along the base of the Churia Hills.

A number of leguminous crops and oil seeds are also grown throughout the region as a subsidiary to paddy and wheat. Among the cash crops, tobacco, mustard seed and potato are popular. Some communities (outside of the study area) engage in growing green vegetables as cash crops which are trucked for sale to other parts of Nepal, such as Kathmandu. Since the establishment of a sugar factory in Lahan, the cultivation of sugarcane (Saccharun officinarum) has increased. Prior to a 1973 international convention against drug trafficking, Siraha was also well known for the production of hashish (Cannabis sativa) as a cash crop.

The principal trees raised privately for their marketable wood are sissoo or sisam (Dalbergia sissoo) and mango (Mangifera indica). The main orchard fruits are mango, leechy (Litchi chinensis), papaya (Carica papaya), guava (Psidium guajava), jackfruit (Artocarpus heterophyllus), custard apple (Annona reticulata) and citrus (various Citrus spp.) in season.1 Seasonal harvesting and sowing patterns are shown in Table 1: Seasonal Crop Calendar.

Recent nutritional research in select communities of the two districts shows that only 15-20% of households are food self-sufficient for the entire year. In fact, only for 50% of households are harvests sufficient more than half the year (Vaidya 1990:4). Food shortages are most severe during the dry spring months of March, April and May. In addition, agriculture in most parts of Nepal can be quite a gamble, with its monsoon climate creating alternating drought and flood conditions. With scanty irrigation facilities, seasonally flooding rivers and spring droughts, the eastern Terai is no exception.

Tree and Forest Resources. The Churia Hills are covered with a highly degraded deciduous forest. Sal (Shorea robusta) and associated species predominate, including khair (Acacia catechu), Indian laurel (Terminalia tomentosa or T. alata), karma or haldu (Adina cordifolia), jaamun (Syzygium cumini), bael (Aegle marmelos), bot dhangero (Lagerstroemia parviflora) and several bamboo species and genera.2

The adjoining Terai was once a virtually uninhabitable and dense malaria-infested jungle, predominated by sal and associated species. Today, in Siraha, only three patches of the original natural forest remain, at Mutani, Ubha and Muksar. These forests cover a total of only 1 300 ha of land. In the early 1980s, under the former Sagarmatha Integrated Rural Development Project, some forest plantations were established on 1 338 ha of land, including portions of the remaining natural forest patches. The intent was to upgrade existing forest, provide more timber and fuelwood resources and stabilize stream and river banks. Tree species in the plantations include khair, sissoo, jaamun, eucalyptus (Eucalyptus camaldulensis), ipil-ipil (Leucaena leucocephala), seto siris (Albizzia procera), bakaino (Melia azedarach), teak (Tectona grandis) and others.

The forest is an important source of supplementary food resources, especially for the landless and near-landless poor of both districts. Major and minor forest products are consumed or sold in local markets and exported (illegally) across the border to India. Forest foods are particularly important to the poor during the most intense food deficit periods (March-May). They include fruits, nuts, berries, tubers, leaves, mushrooms, insects, small animals and birds. The forest also provides fuel and fodder supplements to the farm enterprise, and raw materials (timber and fuel) for small scale rural enterprises and industries. Fuelwood from both common and reserve forests is the principal energy source (see Chapter 3, Table 5: Energy Sources and Annual Consumption Rates, Rural Terai).

Public Services. District administrative headquarters are at Siraha town, in the southwestern corner of the district near the Indian border. Under the former panchayat (elected council) system of government, which still existed when much of this research was conducted, the district was administered by a council of elected representatives from each of the village panchayats. The district panchayat was linked upwards through the zonal administration to the central administration and national assembly in Kathmandu. Since the popular uprising of February-April 1990 (sometimes called the "Movement to Restore Democracy"), much of the panchayat political structure of government has been removed, and a revised system with a constitutional monarchy has been instated. The district administration is headed by a chief district officer appointed from the Ministry of Local Development. He is assisted by district officers from each of the line agencies (forests, soil and water conservation, agriculture, health, education, etc.). In addition, there are offices of the Agricultural Development Bank of Nepal, the Small Farmer Development Programme office, a cooperative programme office and several commercial banks.

The nearest airport is at Janakpur, near the Indian border in Dhanusha District, a two hour drive from Lahan. There are no railways. Public transport is by bus or truck. Private transport is by jeep and automobile on the paved roads and on some side roads during the dry season. The district is bisected by the Mahendra Highway (Mahendra Rajmarg; sometimes called the "East-West Highway"), a mostly paved roadway which serves for transport of local products traded in and out of the district, and for incoming commercial and industrial items. Most inhabitants walk, bicycle or use bullock carts. The public bus system is used for travelling long distances.

Many communities have primary and elementary schools, some have high schools. There are two colleges, the Suryanath Satyanarain Maraaita Campus in the town of Siraha and the Lahan Campus in Lahan. Both are units of the national Tribhuvan University. A campus of the Institute of Forestry (IOF) is located at Hetauda, in Makwanpur District, approximately 200 km west or a five hour bus ride from Siraha. Several youths from Siraha and Saptari Districts are enrolled at the IOF.

Physical Description. In area, Saptari District covers 1 382 sq km, 15% larger than Siraha. Like Siraha, Saptari is also divided geographically into two parts, the Churia Hills in the north (441 sq km, or 32% of the total area) and the flat Terai plain, covering the majority of the land area (941 sq km, or 68%), in the south, here too bordering on the Indian state of Bihar. The highest point is 305 m in the hills, and the lowest point is 61 m on the plain. Prominent rivers flowing south out of the Churia Hills across the district are the Koshi, Triyuga, Balan, Mahuli and Khando. In climate, Saptari varies only slightly from neighbouring Siraha. The average annual rainfall is 1 450 mm. The average maximum temperature is 38º C, the low, 16º C. As in all the eastern Terai, the monsoon, which brings on flash flood conditions, creates havoc with croplands.

Demography. There are 113 village communities (former village panchayats). The total population is 379 055, in 68 919 households with an average of 5.5 persons/hh. Population density is 278.1 per sq km. Like elsewhere in the Terai, ethnic composition and population are heavily influenced by recent migration from the middle hills and North India. Caste and ethnic groups include the Chaudhary (Tharu), Yadav, Bahun (Brahmin), Magar, Rajput and Muslims. The principal languages are Maithili and Nepali.

Economy. The major occupation is subsistence agriculture combined with orcharding and livestock raising. The major crops, fruits, livestock and local industry are virtually identical to Siraha District (see above). The major market town is Rajbiraj (the district administrative seat) in the south of the district, near India.

Tree and Forest Resources. Total natural forest cover is 1 900 ha, concentrated in the Churia Hills and in scattered patches on the plain. The residents of Saptari have comparatively more access to forest than their Siraha neighbours. Almost all natural forest of the district lies north of the Mahendra Highway, with only a few patches remaining south of the road. The existing forest has been over-exploited and seems unsustainable in its present condition. Forest degradation is attributable to fuelwood and timber cutting, fodder lopping and excessive, often illegal and uncontrolled (open access) livestock grazing. There is some community forestry development work for income generation (cash crops) and some small forest enrichment plantings conducted by the district forest offices (DFOs). Major species found in the remaining natural forest stands are sal, khair, asnaa (Terminalia tomentosa), karma, various bamboos and bael.

Public Services. The structure and function of district government is the same as that described for neighbouring Siraha, with district and zonal headquarters in Rajbiraj town. Public and private transport and facilities are similar to those in Siraha. The Mahendra Highway bisects the district and several side roads lead south to the Indian border. There is an airport in Rajbiraj, but service is sporadic. The next nearest airports are two hours drive west at Janakpur in Dhanusha District or three hours drive east at Biratnagar, in Morang District.

The study was conducted in two selected village communities, one in each district. They are Bramahan-Gorchhaari in Siraha and Bakdhuwaa in Saptari. The choice of these sites was by no means random, but was a deliberate selection made by staff of the DIECF Project and the DFOs on the basis of the following needs and assumptions:

Two other less formal assumptions also influenced the choice of the study villages. First, relative ease of access was considered important, especially given the short time available for the study and difficulties of travel. Both sites can be reached by jeep from the Mahendra Highway, though the more remote neighbourhoods and forest areas must be reached on foot. Second, the DIECF Project staff was relatively more familiar with these two communities than with some others. Hence there was slightly more knowledge available about these villages at the beginning of the study.

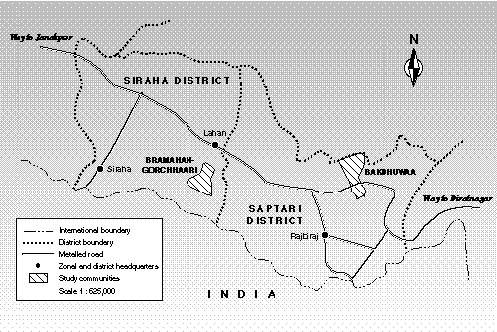

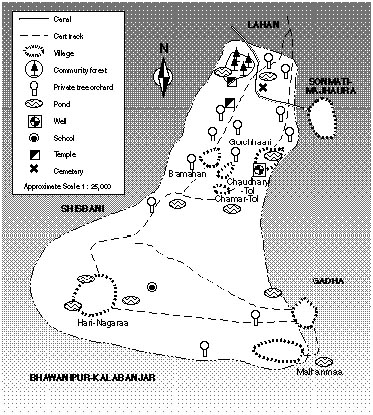

Physical Description. Located between one and three kilometers south of the Mahendra Highway, Bramahan-Gorchhaari is a mixed-caste/ethnic farming community with four distinct village clusters or hamlets: Malhanwa, Hari-Nagara, Bramahan and Gorchhaari (see Map 3 and Appendix B, Table 9, Bramahan-Gorchhaari and Bakdhuwaa compared). The community is readily accessible on foot, bicycle, bullock cart or jeep from the market town of Lahan, situated along the Mahendra Highway. Bramahan-Gorchhaari shares a boundary in the north with the municipality of Lahan.

The terrain is flat, at a mean elevation of 108 m. The soils are loamy. The villages and lanes are extremely dusty during the dry season (February to May) and impassable due to mud during the rainy season (June to September). The hamlets are nucleated, each connected to the others by a series of bullock cart tracks and footpaths past open farmlands and groves.

The impression on first entering Bramahan-Gorchhaari is of rutted lanes and flat fields between scattered homesteads, hamlets and a great many trees of different species, punctuated by mango groves and bamboo clumps. Walking through the village streets, one is struck by the large number of white zebu cattle and dark water buffalo tied or stalled alongside most houses. Cattle and water buffalo are used for animal traction to plough fields and pull bullock carts. There is also a high demand for fresh milk and clarified butter (ghee) which is sold in nearby Lahan bazaar.

Map 3: Bramahan-Gorchhari Community

Demography. Population is 2 342 persons in 486 households, or 4.8 persons per hh, according to demographic figures available from the Siraha DFO. The predominant castes and ethnic groups are the totally landless Musahar (Earthworker caste) with 165 hhs (34% of the total), the Chaudhary (ethnic Tharu, farmers) with 129 hhs (26.6%), and the Mahato (Vegetable Grower caste) with 71 hhs (14.6%). Another eleven groups make up the remaining 18% of households in the community (see Appendix B, Table 10, Households by Caste and Hamlet, Bramahan-Gorchhaari).

Economy. The vast majority of the villagers subsist by farming and orcharding, either on their own land or as tenants on the lands of others. The main field crops are paddy rice, wheat, maize and millet. A fuller discussion of these agricultural activities is given above for Siraha District.

The main orchard fruits are mango, leechy, papaya, guava, jackfruit, custard apple and various citrus fruits in season. Areca nuts (Areca catechu) are also raised for personal consumption or sale in the bazaar (see Table 1, Seasonal Crop Calendar). Farming and orcharding is supplemented by animal husbandry (cattle, buffalo, goats and chickens), and the sale of animal by-products (milk, clarified butter, eggs). Villagers also make miscellaneous crafts (e.g., varieties of split bamboo baskets and mats) for home use and for sale in the market. The main outlet for these items is the Lahan bazaar, at the twice weekly open market. The sale of certain mature trees (mango, sissoo) to furniture makers and brick kilns is also important.

Some villagers work as day labourers in the mills, shops and offices of Lahan, and some work at neighbourhood brick kilns. A few poor people also make bhurra, a kind of tobacco dust from the residue of crushed tobacco leaves. It is packaged in small polythene bags and sold for smoking in the simple hand pipe (chilim) of Nepal.

Access to Trees and Forest. Sources of fodder, fuelwood and wood for farm implements are extremely limited and barely adequate to meet villager needs.

There is a 6 ha community-managed religious forest called Bramahan Jangal. Its use is limited to the poor for collection of leaf litter for livestock bedding and cooking fuel, and of fallen twigs and branches for fuel. At the edge of the forest is a small Hindu shrine dedicated to the god Bramahan, a local deity, cared for by a resident baabaa or holy man. The secular management of the forest is under jurisdiction of the village council.

Landowners rely mostly on trees growing in their home compounds and adjacent to their agricultural fields for fuelwood and other wood products. They supplement cooking fuel with animal dung and agricultural crop residues (stalks and chaff; see Appendix E: Categories of Cooking Fuel). Tenant farmers rely on what they can grow on their home compounds and on any small plots they may own, since rights to trees they might plant on another's land are insecure. The poor and landless, for their fuelwood, fodder and other tree products, depend almost exclusively on what they can glean from village commons and on the government reserve, the Churia Forest, some hours walk north of Lahan.

Animal fodder from trees (leaves) is not a major concern in traditional Terai villages. The exception is found among recent immigrants to the Terai who follow the middle hills custom of lopping fodder trees to feed their livestock. Indigenous villagers, according to the season, graze their animals on the stubble in the fields or stall feed them with crop residues such as rice stalks mixed with bermuda grass cut by hand from the bunds of rice fields or from commons.

Tree resources on commons and in the reserve forest are severely limited, but are of critical importance to the subsistence of approximately 40% of villagers (mostly low caste Musahar) who are both landless and treeless. This is particularly true for the collection of cooking fuel. The DFO estimates that, with no available forest resource other than the tiny religious forest, total forest land available in Bramahan-Gorchhaari is only 0.0025 ha (25 sq m) per capita.

Community Government. Until 1990, local leadership was in the hands of an elected chairman (pradhan pancha) and a council of representatives from each of nine wards. The most recent pancha was a man of the second largest caste (ethnic) group, the Chaudhary, but the ward representatives included men (no women) of other groups, including one from the lowest but numerically dominant caste, a landless Musahar.

Villagers speak of long-standing factional distrust, based on inter-communal rivalry, between the second largest but most powerful Chaudhary group and the third largest Mahato (Vegetable Grower) group. One point of contention is over management and benefits of the religious forest. The Mahato claim that the Chaudhary, under their influential leader, take benefits unfairly without sharing them with others. Some even claim that the leader of the landless Musahar is a "chamchaa" of the former Chaudhary pancha (chamchaa, literally "spoon," refers to a lackey or sycophant of a powerful person). This argument over access to the products of the forest is one indicator of the scarcity and importance of forest resources. Another is the extensive use of the Churia Forest, several hours walk north of the village. Use of the Churia is briefly discussed in the description of Bakdhuwaa community, below, and in the section on Government Reserve in Chapter 3.

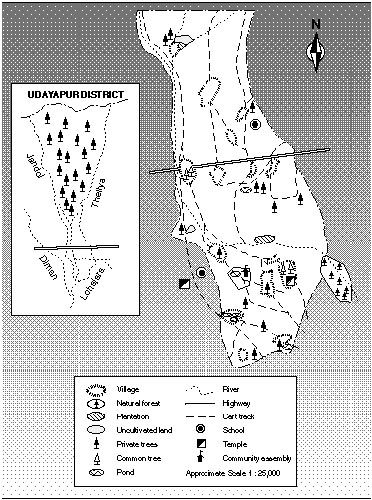

Map 4: Bakdhuwaa Community

Physical Description. Bakdhuwaa community stretches southward from the Churia Hills into the central eastern Terai. The community is bisected by the Mahendra Highway (Map 4). A prominent feature of Bakdhuwaa is the Mahuli River flowing south out of the Churia Hills. The river floods during the monsoon, regularly inundating adjacent agricultural lands and commons with water and sand deposits.

The small Mahuli bazaar straddles the highway on the east side of the Mahuli River bridge. It has a bus stop and various shops and eating establishments, a Hindu temple and a school. Mahuli bazaar is approximately an hour's drive east of Lahan in Siraha District and an hour northwest of Rajbiraj. The elevation above sea level of Bakdhuwaa community ranges from 311 m at the north to 100 m at the south.

The farming conditions in Bakdhuwaa are similar to those of Bramahan-Gorchhaari, but the landscape, particularly north of the road, shows greater relief with the hills and eroded outcrops of the Churia. Unlike Bramahan-Gorchhaari, this community encompasses a portion of the Churia Hills and Forest and the bhabar belt with its poor soils.

Demography. As is common in this part of the Terai, Bakdhuwaa is a mixed-caste/ethnic farming community. There are six distinct villages or hamlets: Mohanapur and Basantapur north of the highway, Ratwada on both sides of the highway and Bakdhuwaa, Bhimar and Chhapki south of the highway. The overall population is 4 258 persons, in 916 hhs, or 4.6 persons per hh.

Bakdhuwaa has two religious groups, the majority Hindus (90%) and the minority Muslims, locally called Miya (10%). The dominant caste and ethnic groups are: Chaudhary, or Tharu (230 hhs, 25% of the total); Bahun/Chhetri, high caste hill migrants (138 hhs, 15%); Yadav, the Milkman caste (135 hhs, 15%); Musahar, the Earthworker caste (105 hhs, 11.5%); and Miya (Muslim, 92 hhs, 10%). Another 10 groups make up the remaining 24% of the households (see Appendix B, Table 11: Households by Caste and Hamlet, Bakdhuwaa).

Economy. In most respects, the economy of Bakdhuwaa is like that of Bramahan-Gorchhaari, described above. There are, however, two significant differences. One is that many recent immigrants from the hills have settled in new hamlets on bhabar lands at the base of the Churia Hills at the north. They practice dairying and use the nearby forest as a source of fodder and for grazing. Another is that Bakdhuwaa has no large town or bazaar as conveniently close to its villages as Lahan is to Bramahan-Gorchhaari. Therefore village-based commercial enterprise is less oriented to outside markets, although some trade is conducted between Bakdhuwaa and the town of Rajbiraj. The former pancha of Bakdhuwaa, a wealthy and powerful Brahmin landowner, is himself from Rajbiraj.

Access to Trees and Forest. Daily access by landowners and tenant farmers to the products of trees and forests is similar to that of Bramahan-Gorchhaari, except that Bakdhuwaa has considerably more forest within its boundaries. On its southeastern boundary, Bakdhuwaa contains a portion of the Kukurharka community forest which it shares with the neighbouring communities of Lohajara and Theliya. The boundaries, and potential management and control of Kukurharka, however, are in dispute. Figures provided by the Saptari DFO indicate that 1 444.38 ha of Kukurharka fall within the boundaries of Bakdhuwaa. Based on this figure, the DFO has calculated forest land per capita at 0.34 ha.

The boundaries of Bakdhuwaa community also enclose a large portion of reserve forest in the Churia Hills at the north. Villager access to this resource is theoretically limited by law, though this is not very strictly enforced. The survival of many landless and treeless villagers is dependent on the Churia. Despite the prohibition, they harvest a wide variety of minor and major forest products. The situation is not unknown to the authorities, but they are virtually powerless to enforce the law. Harvesting the Churia Forest is an example of illegal but largely unregulated utilization.

Community Government. In recent years, until the demise of the Panchayat system, Bakdhuwaa was governed by a representative council of nine ward leaders, headed by a chairman, his deputy and a secretary. The last pancha was a rich Brahmin landowner who was asked, he claims, to come to the community in order to stand for election against a candidate representing the dominant Chaudhary group. The Brahmin owns land in Bakdhuwaa and maintains a residence in Mahuli bazaar. He is supported by the second largest resident group, the Bahun/Chhetris, most of whom are recent migrants from the hills. In effect, the Brahmin's successful election simply replaced the power of one communal faction with that of another. Factional disputes here among communal groups - the dominant Chaudharys, Bahun/Chhetris and Yadavs - reflect concern over allocation of scarce resources, particularly trees and land.

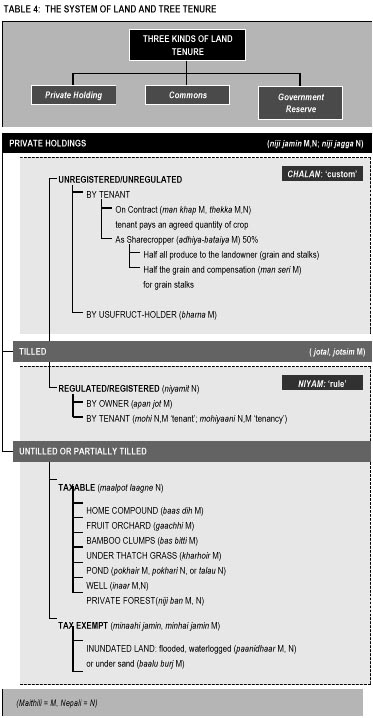

The concept of "tenure niche" (Bruce 1989) guides this study. A tenure niche is a socio-ecological concept used to describe and discuss a variety of options, opportunities and conditions for the use and management of land and landed resources. The following sections of this study follow Bruce's three broad categories of tenure niche: private holding, commons and government reserve (see Table 5: The System of Land and Tree Tenure).

This notion of three tenure niches, however, reflects a certain degree of compartmentalization. While multi-tenurial distinctions are important and do reflect a level of local reality, these distinctions can also be misleading. In the study area, while each distinction is fairly clear to all concerned, linkages and interrelationships across the tenure spectrum are more important. Villagers tend to define each niche somewhat broadly. Private holdings and commons, for example, include water (ponds) as an important element; and government reserves encompass more than forests to include land for roads, schools, government office buildings and other installations. Each category has a significant meaning in relation to trees and access to tree products. For example, trees grow on commons and on government lands regardless of whether they are pond banks, "wastelands," reserve forests or school grounds, and it is typically the poor who most benefit from access to these resources.

It is common in agrarian societies to measure wealth in terms of private land holdings and agricultural production. Researchers often look only for these indicators, assuming that they are sufficient to distinguish between levels of wealth. A recent nutritional baseline research report from Siraha and Saptari, for example, quite typically defined "large farmers" using as its only criteria the ownership of two or more hectares of land (Vaidya 1990:4). The rapid appraisal findings in these same districts, however, indicate that in the eastern Terai ownership of trees on holdings is an equally important indicator of wealth. Tree tenure appears to be a critical element in the maintenance of social and economic status, power and prestige, and in the local perception of wealth and success in agricultural activity.

Tree ownership and land holdings are, of course, closely correlated - to grow trees one must own sufficient land. But when asked to define a "wealthy farmer," villagers often responded in terms of tree and orchard ownership.1 This ownership is usually calculated in terms of the number of small, scattered orchards (gaachhi) on holdings of from 0.05 ha to 1.5 ha in size. A gaachhi is literally any tree field, tree garden or small plantation that is usually, though not necessarily, planted in fruit-bearing species. Some orchards include non-fruit bearing species, like sissoo, valued mostly for its timber.

Virtually all farmers try to plant some trees as an investment, for profit. Medium and small farmers typically plant a variety of trees on their home compounds and on the edges of their agricultural fields. The number of trees planted ranges from two or three within the home compound area up to several dozen on widely scattered holdings2 Wealthier farmers plant whole orchards on large plots; for them having several orchards (up to five) seems to be a common goal.

Some households with larger holdings practice extensive tree farming or orcharding. Their incentive lies in the high market demand for wood, especially fuelwood and timber for construction and in the government's recent reduction of taxes on land brought under tree production (Joshi 1990; Dixit 1990). In the past, mango was the most popular species, but sissoo, though non-fruiting, has recently become very popular because of its value as construction timber (window frames and door lintels) and in furniture making. While some farmers plant only mango or sissoo, it is more common to find mixed orchards, with mango in the main plot and sissoo around the border. The sissoo is extensively lopped for fuelwood during the winter and the leaves are fed to goats. By border planting and lopping, the shade effect of sissoo over the mango fruit is diminished. The issue of the shade effect of trees planted on the boundaries of agricultural fields is of great concern to farmers. There are customary rules about locating trees whose shade might affect a neighbour's crops (see textbox The Shade Effect of Trees). Sissoo, furthermore, serves as a windbreak for the mangos.

The planting of mango and sissoo is well justified from an economic point of view. In the short term, mango provides an annual income from the fruit (for which this part of the Terai is famous) and, in the longer term, the tree provides timber and fuelwood for both home use and income generation. Sissoo trees have less short- term benefit, limited to some forage and firewood for home use, but provide a handsome return on investment in the long term.

The Shade Effect of TreesThe farmers of the eastern Terai are very conscious about the shading effect of trees in agricultural fields. Sunlight affects the growth, development and hence the production of crops, and there is a significant reduction in agricultural production due to the lack of sufficient sunlight in tree shaded areas, especially in the case of rice, maize and wheat. There are no rules in Nepali law for dealing with the adverse effect of the tree shade from one farmer's fields on his neighbour's crops. In this case, customary law is followed, under a local rule known as "east-south." Under this rule, the farmer has the right to plant trees only on the east and south borders of his fields, not on northern or western borders. By this rule, the farmer's trees will not cast shade on the neighbour's crops. This rule does not apply where the north or west boundaries are adjacent to non-agricultural lands. In addition to this custom, there are several other local technologies to reduce the shade effect on crops. One example is the pattern of planting sissoo trees in mango orchards. Sissoo trees are often planted on the edge of the orchard where they serve as wind breaks, but they are carefully spaced so that they do not adversely shade the mangos which require considerable sunlight for fruiting. |

While the intensity of orchard farming (total number of trees and groves) is slightly higher in Bramahan-Gorchhaari, reflecting a larger number of wealthy farmers and a greater need for trees there, the practice of mixed mango-sissoo orcharding is common to both the study villages. A good example of local response to the profitability of tree farming is Bakdhuwaa, a hamlet which lies north of the highway. There, a number of farmers have begun buying seedlings from government nurseries and growing them as cash crops, earning a substantial profit at maturity (see textbox Growing Sisso Trees for Profit in Bakdhuwaa).

There is a critical relationship between the perception of secure tenure on a piece of land and what one plants on that land. Not all farmers are in a position, legally or practically, to invest in trees. Landless tenants fall into this category.

Poor farmers with little holdings, and those who depend mostly or solely on their work as tenants on the lands of other owners, are at a disadvantage. Farmers in Terai villages tend to plant trees only on land on which there is no confusion about rights; that is, on property which is legally registered to the cultivator as private agricultural land or homestead. A tenant who cultivates the land of another person has no tenurial rights under law to any trees he might grow there (Nepal 1964, 1979).

Tenants pay their rents, in law and by tradition, with a fixed percentage of the agricultural produce (i.e., in grain and grain by-products). The amount is fixed relative to the category of land. There is no provision to pay rents with trees or tree products. Even if a tenant were tempted to invest in trees, he would have great difficulty meeting his obligations to the landowner, given that grain is the accepted mode of payment. In addition, because the lands a tenant cultivates are often at some distance from his home compound, he would have this added difficulty in managing trees, especially during their first critical years as small seedlings and saplings. Thus those poor whose need for trees is the greatest, and who have the most to gain by investing in trees and orchards, are effectively forced to remain treeless or near treeless.

While penalized by all the disincentives to invest in trees on land under tenant cultivation, smallholders and tenants still seek every secure opportunity to plant them. Some very poor villagers who own less than 0.1 ha of land were observed cultivating up to ten trees in their home compounds. They fully realize the long term value of trees as a form of banking or security against contingencies (see textbox Banking on Trees in Gorchhaari). None, however, was observed investing in trees on the land of others where they labour as tenant farmers.

Growing Sissoo Trees for Profit in BakdhuwaaOver the past three years, in the hamlets of Bakdhuwaa north of the Mahendra Highway, farmers have begun planting trees for future profit. Most farmers in this part of the community are recent immigrants (Bahun/Chhetri, Rai and Magar) from the hill districts to the north. Most practice dairy farming. They also plant some fodder and fruit trees on their home compounds, but depend more on easy (though illegal) access to the nearby Churia Forest for most of their timber, fuelwood, fodder and thatch grass needs. Many farmers express keen interest in planting more trees on their private lands, after hearing of high profits made by a local Chaudhary (Tharu) farmer who sold three mature sissoo trees recently. The story got around that he had earned an astounding NRs 100 000 (USD 3 400) for three trees - certainly an exaggeration, but one which makes the point that farmers perceive great opportunity in tree farming. Several farmers have tried to copy the Chaudhary's enterprise by planting sissoo in small private plantations. But given the difficulty of protecting young seedlings from drought and livestock grazing, only a few so far have been successful. One of the community's more active small tree farm owners is a Brahmin woman who expects a big profit when she markets her sissoo trees in a few years. Foresters at tree nurseries established by the Terai Community Forestry Development Project report that they have difficulty keeping up with the demand for sissoo seedlings. A farmer can buy one seedling for 53 paisa (NRs 0.53; approximately 1.8 US cents) at a nursery. Although it is not an official policy to charge for seedlings, some government nurseries in the Terai have started to charge a small amount per seedling. A sissoo tree is considered mature for timber in 50-60 years, although they are frequently sold in the villages for fuel as early as 15-20 years. Currently, a 15 year old tree sells for NRs 2 000 (USD 68), a 20 year old sissoo fetches up to NRs 3 000 (USD 103), and a 30 year old tree sells for NRs 14 000 (USD 500). The incentive to invest in these trees is high. |

The poor face another difficulty as well, based on local perception about tree tenure. The law requires that private forests be registered with the DFO authorities, but very few private forests are ever registered. Government nurseries distribute tree seedlings free of charge (though some Terai districts have started to charge a small amount) and require each recipient to sign for them. Villagers were unwilling to do this, out of fear that their signature in the register serves, in effect, as an act of registration of their private forest and that by so doing they may loose their rights to both the trees and the land on which they are grown.

Normally, raising and using trees privately on holdings poses no real problems; it is ignored by the authorities. But to sell fuelwood and especially timber from private holdings, the farmer is required to engage in a two step petition process. He has first to secure a recommendation from the local community leader, and then to carry that recommendation to the DFO to buy the permit. For the poorest and weakest farmers this process can be formidable, and it is viewed with suspicion. Bribery is sometimes necessary, making it all the more difficult for them. Few farmers fully comply with the law and only a few transactions involving the sale of tree products from private lands are handled with a clear and bribe- free permit.

Banking on Trees in GorchhaariMany farmers of Siraha and Saptari Districts plant trees on their fields and home compounds as a form of security against future anticipated (usually unspecified) need. The most popular species are mango and sissoo, valued in the short term for fruit (mango), fodder (sissoo) and fuelwood (both), and in the long term for the substantial profit they bring when sold for construction timber or furniture-making (textbox Growing Sisso Trees for Prodit in Bakdhuwaa). There are several categories of contingency for which the rural poor may use trees or tree products: social conventions and ceremony, personal and communal disaster, physical incapacity, unproductive expenditure or investment and exploitation by the powerful (Chambers and Leach 1989). While a few farmers in the study area spoke in very general terms of planting trees for future use, several cases were also noted of planting trees for specific contingencies, e.g., on private holdings for anticipated wedding expenses, and on commons to provide wood for funerals for the very poor (textbox Trees on Commons for the Funerals of the Poor). Trees for WeddingsDevidas lives in Gorchhaari hamlet of Bramahan-Gorchhaari village. He is the youngest of four brothers, sons of a poor low-caste tenant farmer (mohi). Devidas's father planned to plant four mango trees on his small parcel of land, one for each of his sons. His intent was to reap the fruit in the short term and sell the mature trees to pay for some unspecified, but ever-threatening, contingency later. Unfortunately, he died before he could complete the task and only two seedlings were ever planted. After his father's death, Devidas and his elder brothers divided up the family's few assets, a house and a small plot of land. In time the older brothers married, putting each man into debt and further reducing their joint inheritance. When it was Devidas's time to marry, there was nothing left to pay for it but the two mango trees. So the trees were sold, and Devidas was married. Older now, with his own growing family, Devidas thinks constantly of the future and of the financial difficulties he and his own three children will face - not least the costs of their weddings. Like his father, he is a poor farmer; he owns only a small home compound, and works as a tenant on the fields of others. Remembering the wisdom of his father, Devidas has begun planting trees on his own small parcel of land. But unlike his father, he is very clear about how to use those trees: "I planted them for my children's weddings," he says. He chose the more valuable sissoo to begin with, but intends to plant some mango, too, as soon as he is able. |

The expansion of orcharding and tree farming practice, as described, are forms of agroforestry. By definition, agroforestry is any land-use system combining woody perennials (e.g., trees, shrubs, bamboos) on the same management unit with herbaceous crops and/or livestock, either in some form of spatial arrangement or temporal sequence, or both. It has been noted that "in the Terai region of Nepal with its rapidly increasing population and decreasing forest resource base, agroforestry holds real potential for increasing the overall productivity of the limited land base" (Joshi 1990:10).

There are many variations of agroforestry. There are several traditional, distinctive patterns for planting trees, singly or in groups or groves on both private holdings and on commons. The most usual are patch planting, line planting, scattered planting and hedge (or live fence) planting. Sometimes, too, naturally generated trees are left to grow and may even be protected and nurtured until utilized.

Patch planting is done on private farmlands and on commons. Generally, a piece of farmland is set aside for this purpose not very far away from the house compound, so the farmer can keep watch on the trees and tree products. Patch planting is usually done by those wealthier farmers who have at least 2-3 ha of land. It is also common on pond banks (private or commons). Mango, sissoo and bamboo are the most popular species.

Line planting is generally done on the edges of mango groves or on the bunds of cultivated fields or sometimes on the boundaries (like a roadside or pathway). Species of choice are sissoo (in mango groves), jamun, sohijan (Moringa oleifera) and bansibat (Delonix regia).

Scattered planting is generally done on home compounds and other farmland by small farmers and the near-landless. Many naturally-generating species are nurtured in this system, especially fruit and nut trees and those which provide fuelwood and timber.

Hedge planting is popular to protect home compounds and farmlands against livestock. Hedge plants (live fences) are planted closely in a row and are sometimes augmented by dry fencing materials, especially loppings from thorny trees and bushes. Altogether eighteen species of trees for live and dry fencing were identified during the study.3

A total of 107 species of "trees" (gaachh, the local taxonomy which includes tree-like species of climbers, bamboos and plantains) were recorded in the two villages of this study and in associated forest areas (see Appendix D: Tree Species of the Eastern Terai). Seven types of use were identified: major and minor fuelwood; fodder; construction, furniture and implements; live and dry fencing; edible products; sacred, medicinal and ornamental uses; and miscellaneous uses of minor importance.

Most species serve multiple purposes. The most useful are often found or planted close by. Those noted for their sacred, medicinal and ornamental properties and some that yield edible products, especially fruits, nuts and blossoms, are usually raised on home compounds for easy access. Some species used for tool-making and fencing are also grown on farmers' plots or in home compounds, while others are harvested from common lands or from the Churia Forest.

Bamboo is often used in the agroforestry mix. It is often called the "poor man's timber," but is very popular nonetheless. It is a common "tree" (gaachh) crop. It may be seen growing in large and small groves on many unirrigated upland plots, some quite close to the farmers' home compounds. Bamboo is a multipurpose crop: among others, the culm (main stem) is used for poles and posts in construction and for making dry fences, and the leaves are burned as an alternative cooking fuel.

There are a number of ways, both by law and by custom, regulated and unregulated, for passing on or gaining tenure in private holdings and private trees. Table 2 lists the standard practices of transfer and conversion of tenure. One acquires ownership of private holdings in any of four ways. The discussion includes several examples of complications that arise between law and custom.

| TABLE 2: TRANSFER AND CONVERSION OF TENURE |

|---|

| ACQUIRING PRIVATE HOLDINGS (arjit N) (Maithili = M, Nepali = N) |

|

| CONVERTING PRIVATE HOLDINGS TO COMMONS |

|

| CONVERTING GOVERNMENT RESERVE LAND TO PRIVATE HOLDINGS |

|

| CONVERTING GOVERNMENT RESERVE LAND TO COMMONS |

|

Usually when lands are sold or purchased, or when sons divide their patrimony, the trees are included. In an example of the contrary, however, after a rich Chaudhary man with four sons died, all of his agricultural land and trees were distributed to his four sons through inheritance (see number (3) below). The man had planted trees on several parcels of private holding, mostly on the bunds of rice fields as well as around a private pond. When one son then chose to sell his share of land to a brother, he kept the rights to the trees for himself.

Sometimes lands are sold without registration, outside of the law. This may occur under situations of encroachment when the land is illegally cultivated, or in cases of unregulated usufruct. Ownership and tenancy are sometimes faked. This practice dates back to national land reform in the 1960s. Under land reform, the upper limit of holdings in the Terai was set at 25 bighas (approximately 17 ha). Some farmers actually hold more land and get around the ceiling by keeping some of it out of cultivation or by giving it to others, usually the near-landless, to cultivate. Tenant rights in such cases are nonexistent. Some unscrupulous local political leaders, usually elected from among the wealthier farmers, support unregulated encroachment, usufruct and tenancy in return for support during an election.

Inheritance of trees on some categories of land may come into dispute. In one example, certain rice lands were partitioned, inherited by several sons and duly registered. However, some small sissoo trees unequally distributed around the bunds of some fields were ignored. Later, when the trees matured, their value was recognized and a fight ensued over ownership, as all the brothers claimed equal share as a belated extension of the patrimony.

Examples were observed of encroachment on unclaimed commons by poor villagers, especially the landless. These farmers sometimes lay claim to such land, on roadsides for example, by planting trees or building a house and settling as squatters, in an attempt to secure tenure as a private holding. Success is usually dependent on a combination of personal power and prestige, persistence, and the backing of a powerful person in the community or of a caste group or faction.

In the past, this type of encroachment rarely succeeded. Any trees the poor squatters might have planted, for example, were simply claimed by the community leaders as common property, and their hovels were ignored, or in some cases, torn down. More recently, however, the tendency is to allow use rights to persons planting trees on commons and to ignore the squatters or quietly allow them to persist unregistered. There is no clarity in the law regarding this type of situation, although local public opinion sometimes has a positive effect.

In Bramahan-Gorchhaari, for example, a man planted several mango trees on unclaimed, abandoned common lands a few years ago. When the trees were three or four years old, he got into a dispute with the village council chairman, the pancha, who sent men to cut the trees down. Some other villagers were outraged and spoke up against the deed, pointing out cutting down young trees was wrong on religious grounds, as a sin, and on moral grounds, as wasteful. Encouraged by the public outcry, the tree planter filed a complaint with the District Forest Officer who fined the pancha for the offense. The village then passed a rule that anyone caught destroying seedlings or young trees would be required to replace them.

Besides these four ways for transferring rights to private holdings, land or trees between individuals, there are also means for transferring tenure between categories. Sometimes private land is converted into commons. The conversion of privately built ponds for merit and tax exemption, for example, is discussed under the section on Commons, below. Government reserve land can also be converted to private land by encroachment (above), and, in the case of community forests, to commons by the legal process called "handing over" (sumpieko). However, the handing over refers only to limited usufruct rights and management responsibilities, as defined in a management plan, and not to tenure.

Tenancy on private holdings is categorized according to three criteria: whether the land is tilled or untilled, regulated or unregulated and managed according to custom or modern law.

Land may be tilled according to regulations or in violation of the regulations. Unregulated tillage is practised in one of two ways, by tenants or by usufruct-holders.

Unregulated Tillage by Tenant. Under unregulated tenancy, tenants are distinguished according to whether they are working on contract or as sharecroppers. In neither case is the tenancy arrangement recognized or protected by law. A contractor pays the landowner an agreed-upon rent equal to more or less than half the crop. A sharecropper pays precisely half the crop. The sharecropper has two choices in paying the rent. He can either pay half the grain crop and half the grain stalks produced on the land, or he can pay half the grain and compensate in other ways for the stalks which he may wish to keep for himself.

Grain stalks are valuable as feed and bedding for livestock, and as a main ingredient in one type of cooking fuel made with dung (see Appendix E: Categories of Cooking Fuel). Rice stalks are the most valuable. Some owners settle with their sharecroppers for an approximate equivalent in more grain, some in cash, and some do not require compensation for grain stalks. In a straight sharecropper system of rice production, for example, half the production of paddy and stalks is paid to the landowner. If the tenant wishes to keep the stalks for his own use, he compensates by paying an additional percentage. Traditionally, this payment was one seer per maund. A seer equals 1/40th of a maund. Nowadays, the seer is fixed by law at 0.876 kg, and the maund at 40 kg.

Unregulated Tillage by Usufruct. The allocation of use rights, or usufruct, is usually obtained by loaning money to a landowner who puts up land or trees as collateral security. Prior to the Land Reform Act of 1964, the government recognized two systems of security on loans. Under the first, the borrower gave usufruct rights on the land or trees to the moneylender in lieu of interest. The moneylender held usufruct rights to the collateral properties for as long as the debt remained unpaid. Under the second system, the borrower put up no collateral but, instead, paid interest on the loan. Thus, he retained all rights to his private holdings. While these two systems are no longer recognized by law, the first system based on collateral and usufruct is still customarily practised in the eastern Terai.

Regulated Tillage. Land tilled according to tenancy provisions set down in the legal codes is categorized in two ways: that which is tilled by the landowner, called owner-tilled, and that which is tilled by a tenant (formally registered) who pays a portion of the produce back to the owner as rent. The amount of rent varies according to the category of land cultivated. There are four categories, as shown in Table 3: Land Productivity and Rents in the Eastern Terai.

| TABLE 3: LAND PRODUCTIVITY AND RENTS IN THE EASTERN TERAI | ||

|---|---|---|

| Categories of land by productivity | Rent on lowland fields by maund per bigha (1 maund = 40 kg, 1 bigha = 0.67 ha) |

|

| Dhanhar (N) (paddy field) |

Bhitt Pakho (N) (drier field) |

|

| awwal* ("first," highest) | 15.0 | 8.5 |

| doyam ("second," moderate) | 11.5 | 6.5 |

| sim ("third," poor) | 8.5 | 4.5 |

| chahaar ("fourth," very poor, usually not in cultivation) | 5.5 | - |

| * The terms used have come into Nepali legal usage from the court terminology of India; their origin is Urdu/Persian. | ||

An important distinction in considering tenancy is that between owners and tenants who manage the land according to local custom and those who follow the rules set down in the legal codes. This distinction is noted on Table 4, in the boxes identified as chalan and niyam.

Two types of untilled or partially tilled private holdings are recognized by the law: those which are taxable and those which are declared tax exempt.

Taxable private holdings are divided into several types: home compounds, agricultural fields, fruit orchards, bamboo clumps, thatch grasslands, ponds and wells, and private forests (see Table 4). Only tenants cultivating agricultural fields of a registered landowner are recognized and given tenancy rights according to law. Those who cultivate land in ways not recognized by law, that is by customary tenancy, have no legal rights to the land cultivated or to the trees on the land. A tenant cultivating another person's homestead is also without legal tenancy rights4

Tax-exempt private holdings are defined as land that is rendered useless by inundation, either filled in by river sand or by water. Certain categories of ponds may also be declared tax exempt (as discussed in the section on Commons, below).

Landowners face certain difficulties in turning their lands over to tenant farmers. The lack of clarity and frequent changes in the land laws enacted during the past few decades (particularly land reform) have created a situation of insecurity and mistrust. This has led to labour scarcity and consequently to increased private tree farming.

Both tenants and landowners feel insecure and mistrustful of each other for various reasons, particularly under the prevailing systems of unregistered, hence unregulated, tenancy, including contract tenancy and sharecropping (Table 4). The landowner fears that his tenants may attempt to legally register their tenancies in their own names, hence diminishing his control and ultimately his profits. The tenant, on the other hand, must live with the insecurity of his tenancy under customary rules and the vagueness of current laws.

As alternative employment becomes available in the towns and countryside of the Terai and in neighbouring India (in small industry for example), many former tenants are leaving the land. Landowners are experiencing labour scarcity in the face of these off-farm labour opportunities now opening up for their former tenants and hired help. In addition, many younger, relatively wealthy and well educated landowners have become disinterested in the traditional agricultural enterprise.

The result of these trends is that many landowners are converting their previously productive farmland into less labour-intensive orchards and tree farms. Even in this, however, landowners face problems resulting from local custom and practice. Damage to young seedlings by livestock is high due to the practice of turning cattle and goats out to graze freely and roam unrestricted in the fields during the dry months of March, April and May. Similarly children are typically allowed to eat orchard fruits uncontrolled. This creates a particular problem for the new orchard owner intent on managing his crop for commercial sale.

For obvious reasons, treelessness is closely correlated with landlessness. An estimated 40% of the population is landless in Bramahan-Gorchhaari and 20% in Bakdhuwaa. The majority of the landless are members of the Musahar (Earthworker) caste, a group found in the eastern Nepal Terai and in the adjoining districts of the Indian state of Bihar.5 Musahars are at the very bottom of the Hindu caste system. Their traditional occupation is as earth workers, digging fields and performing works of construction and labour for their more well-to-do neighbours.

Musahars rarely own farmland and may not even own the land on which they have settled and built a hut. In Siraha and Saptari, most Musahars are settled on unclaimed common land, such as a roadside. Their compounds cover from .065 to .130 ha of land each. They have settled with the hope that their compounds may possibly be registered by the land revenue office some time in the future. As they usually settle in clusters, they can exercise a measure of power as a distinct group. The unregistered lands on which their home compounds are clustered are called village-blocks.

Where there is sufficient land near their hut, some Musahars have planted fruit trees, like mango, papaya, custard apple and guava. Some have also planted commercial species, like sissoo, gulmohar (Delonix regia) and teak. They believe that by planting trees, they will have exclusive use rights as well as a small measure of security in their claim on the land.

The Musahars' self-perception is one of complete poverty. As a consequence of their landlessness, they are almost totally dependent on the products of the natural forest of the Churia, except during the peak agricultural planting and harvesting seasons when they seek employment as field labourers. Since they have no cattle or buffalo, they have no ready sources of dung for cooking fuel. Hence, their dependence on the forest and commons is critical. They collect firewood in the forest for not only home use, but also for sale. This and agricultural labour are their two major sources of revenue, though some Musahars of Bramahan-Gorchhaari have found alternative employment in a brick factory near the town of Lahan.