Community Forestry Field Manual 5:

Selecting tree species on the basis of community needs

by Katherine Warner; Edited by Daniel Shallon

The Forests, Trees and People Programme, coordinated within FAO by the Community Forestry Unit (CFU) of the Forestry Department, focuses on strengthening local communities' efforts to improve the management of their forest and tree resources. The selection by the community or individual households of trees to plant or to retain (by protecting or avoiding to cut an existing or naturally growing tree in order to use its products and services) is a key aspect of tree management. The decisions leading to selection of particular trees are influenced by a number of factors, most of which are more related to social and economic issues than to technical considerations.

When the CFU took a close look at recent forestry projects which involved tree-planting by the community, it was quite apparent that some had been popular with farmers because the planted or managed trees were useful to them, were placed in a situation that suited the local land use patterns, and required a management regime that was compatible with the labour and input requirements of the entire production system. Yet it was equally obvious that many projects had been designed without adequately looking at the function trees were to play in the rural economy, nor at the distribution of the costs and benefits of a tree and its planting location.

In 1991, FAO published Community Forestry Note 9: Socioeconomic attributes of trees and tree planting practices, by John B. Raintree of the International Center for Research in Agroforestry (ICRAF). This document presented a new approach to understanding the factors influencing tree planting and tree retaining practices in local communities, and it forms the basis for the present field manual. Following this, the CFU produced a video entitled "What is a Tree? - The functional approach to tree species selection," which considered the closely related issue of the many uses to which trees are put by traditional users. In view of the enthusiastic reception given to these documents, it was felt that there was a clear need for a practical field manual for selecting trees for community forestry projects on the basis of community needs and capacities, as well as the usual technical factors.

The manual has been developed by Dr. Katherine Warner, an anthropologist with extensive experience in community forestry, currently working at the Regional Community Forestry Training Centre (RECOFTC) in Bangkok, Thailand. It translates the concepts of the earlier Community Forestry Note into a practical methodology for exploring the physical and socio-economic situation of a community and then using this as a basis for selecting trees for planting. Dr. Warner, who has worked for many years on the interface between social science and forestry, has used the methods presented in this field manual in field work in several countries and situations in Africa and Asia, some of which are presented as case studies in Appendix 1.

As in the case of other Forests, Trees and People Programme activities, the methods described in this manual lay a strong emphasis on community participation. Understanding community needs is highly dependent on the rapport which is established between the field worker and the local community. The active involvement of the community in the selection process is important to the quality of the results which can be obtained.

This field manual is being produced and circulated with the intention that the application of its techniques will lead to revision and enrichment based on experience gained in different regions of the world. Readers and users are therefore encouraged to send their comments and suggestions to The Community Forestry Unit, Forestry Department, Food and Agriculture Organization. Viale delle Terme di Caracalla, 00100 Rome, Italy.

Marilyn W. Hoskins

Senior Community Forestry Officer

Forestry Policy and Planning Division

Forestry Department

The purpose of this manual is to help field workers to work with a community in order to identify the tree species that would best serve that community's needs. A growing number of projects and programmes are recognizing that

The species chosen for tree-planting projects should reflect the needs and priorities of local communities.

Tree planting requires more than just planting trees. In most communities, tree planting involves a complex sequence of decisions regarding not only which trees should be planted, but also:

To be effective, the field worker involved in community forestry must understand the community in which he/she works and have a thorough knowledge of local tree planting and management practices.

As the focus of community tree-planting projects shifts toward concentration on community needs, the role of the field worker is also changing. Rather than simply promoting tree species previously chosen by the tree-planting project, the field worker should work with the project's intended beneficiaries using a participatory approach, in order to elicit the community's own view of its needs and constraints.

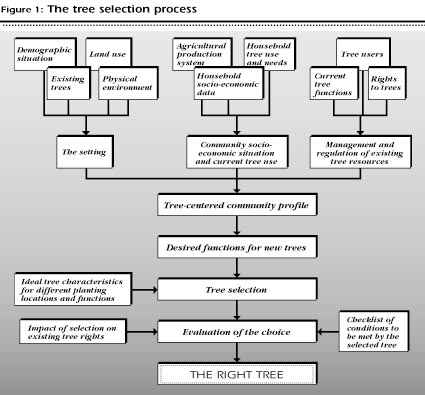

This new role requires the field worker to have expertise in collecting and analyzing information concerning environmental, social, economic and other factors, as well as skills in community extension. Working from this information, the field worker (bringing technical expertise and new options) and the members of the community (bringing local technical knowledge and sensitivity to local conditions) can select among several options of tree species and tree-growing technologies. The objective is to provide the greatest possible benefits to the community (see Figure 1).

Projects and programmes are becoming more participatory in orientation: rather than telling communities to plant preselected tree species in a preselected location, more and more often they try to work with the community to determine the tree species and planting sites that will best fit its needs. If the project activity is to be sustainable (to survive and continue to grow after the end of the project itself and of external funding), it must involve the community members. These beneficiaries must own the project; it should not just be someone else's plan for them. The more the field worker is able to support and facilitate the community in planning and implementing the project, the more likely that this sense of ownership will be created.

There is significant variation in the degree of participation of local communities in community forestry. At one end of the scale, and gradually becoming less widespread, are community forestry projects that are planned and implemented by government agencies, in which "participation" refers to the community providing the labour for planting the trees. At the other end, and still not as common as they should be, are projects in which the planning, implementation, management and distribution of benefits are decided by the community, in a facilitating policy environment (where government policy supports and encourages participatory development) and with the support of government technical personnel and field staff. Currently, most projects and programmes fall in between and involve some degree of joint participation by government and the community (Vergara et al. 1986).

This field manual shows how to create an accurate portrait of the community, its use and management of tree resources, and its current and projected needs. It also shows how to analyse this information and use it to select the right trees for the community.

Rather than beginning with the trees and developing strategies to get the community to plant them, the approach of this manual is to focus on the community and its needs and identify what potential benefits trees can provide. Household decisions will determine the level of implementation and sustainability of any tree-planting project, and these decisions are based on an assessment of whether the household will benefit (economically and otherwise) from the proposed activity. If it does not benefit (or it is unaware of the benefits), it lacks incentive to take part in tree-planting activities. For projects to be successful, communities and households must perceive a potential benefit in planting trees.

In order to determine the tree species which will offer the most benefit to the most people, the field worker and the community will work together to identify what tree products and services (functions) are needed. The process begins with the gathering of relevant information regarding the community and the present role of trees. The natural environment and the social environment together determine the existing opportunities and the limitations in choice of species. Once the desired tree functions have been determined, the field worker's task is to work with the community to identify potential tree species and critically assess which of these species would be most appropriate for the community.

The ability of the field worker to work with the community is crucial for project success, but it is not sufficient in itself: a project requires technical expertise as well. In this manual the role of the field worker is to use his/her own technical expertise to help the community identify tree species that will fit both its needs and its physical environment. By working together, both the field worker and the community should gain knowledge from each other. The combination of local knowledge and outside expertise provides a better foundation for programme development than either one can provide by itself.

Assumptions: This manual has been prepared to provide guidelines for the field worker in a tree-planting project or programme. Some assumptions have been made regarding this project or programme:

The site of the project has already been determined, so guidelines for choosing a project site are not needed. (If a site is not selected or if additional sites are needed, guidelines for selecting project sites can be found in Davis-Case 1989).

Although the general purpose of the project has been determined (tree planting), the actual formulation of the project design (in this case, mainly the selection of tree species and planting locations) has yet to take place.

The project will be participatory in orientation. In other words, the choice of species, location, and tree-planting objectives will be made by the community, with the support and assistance of the field worker.

In most cases, the main interest of the project is to assist the most disadvantaged groups in the community (the poor, minorities, female-headed households, etc.).

The manual attempts to provide a clear explanation of the process of identification of appropriate trees species. To assist this process the manual also includes worksheets that can be used by the field worker for collecting and analyzing information from both secondary sources (government documents, project reports, etc. - see Appendix 3) and the community.

Although the primary purpose of the manual is to assist in the selection of tree species, it can be used for other purposes as well. For example, in a project with preselected tree species, the field worker still needs to determine the niches and spatial arrangement of the trees and consider if there would be any tenure conflicts. The worksheets concerning these topics can be used to gather the information needed for the analysis and planning.

Reflecting the range of community participation in community forestry projects, the role of the field worker may include being a facilitator (initial suggestions, providing expertise not available in the community), a primary decision-maker (authority to decide the tree species after community dialogue), or an extension agent (preselected tree species, location, and community). A field worker in any one of these roles should be able to utilize the methods and the worksheets in this manual to obtain the information that is needed for a variety of uses.

In order to use this manual effectively, you must first have a clear understanding of the kind of information you are seeking. The objective is to obtain enough of the right information to help the community and its members to make a competent decision.

The most common errors in information collecting are:

What is wrong information? "Wrong" information refers to information that will not answer the question which you are trying to answer, either because the wrong question is asked or because the right question is asked to the wrong (inappropriate) group.

A field worker needing information in the current use of trees in the community decided to use Sample Worksheet 10 ("Current function of trees") in this manual. However, the field worker discussed tree utilization only with men rather than with both men and women. The information was therefore incomplete and did not fully answer the key question, "what is the current tree utilization pattern in the community?" The right questions were asked to the wrong people: women (an important user group) were left out.

What is more information than is needed? The attitude of "the more information the better" is a common one, and it may seem difficult to challenge. However, spending scarce time, effort and resources on gathering information that is not essential is a luxury that very few field workers or projects can afford. In spite of this, it is common for more detail to be gathered than is needed. Attempting to get correct information concerning accurate crop yields, precise income, exact distances and times for transport, and so on, can take hours and days of your time, and yet the information is seldom reliable, and often not even useful.

What is more useful than unreliable detailed information is carefully chosen specific information. Knowing whether a family harvested enough of a crop to feed itself through the year is enough for the purpose of tree selection, while knowing exactly how many kilos of each crop were harvested per hectare is too much. Knowing a household's sources of income is all you need for most uses, while learning accurate income data is difficult to achieve and is unnecessary (see Sample Worksheet 8).

Collecting wrong or unnecessary information is the result of not understanding what information is most important. This is usually because not enough thought has been given to why the information is needed. Before starting to gather information, ask yourself:

Why do I need to know it?

and

How will I use the information?

Each section of this manual, along with its sample worksheet, can be used either by itself for a particular use, or in combination with other sections. Many users will not need to complete every section in order to carry out their role as facilitator for community tree selection. The decision on whether to use a particular worksheet, or on what combination of worksheets to use, will depend on a variety of factors, as can be seen from the following situations.

If you work in the community on a regular basis, and already have a clear idea of the land-use map of the village, you will not need to complete Worksheet 2. Nor, probably, will you need to go through the questions in Worksheet 7 on agricultural production systems. However, it will presumably still be useful to do the transect (Worksheet 4) to get more specific and detailed information on tree location in the village territory.

Likewise, if you know that you will be planting trees which are already present in the area, you will not need to use Worksheet 6 on the local climate and soils, since you already konw that the tree will grow under local physical conditions. If you will be planting trees only on private land, you may not need to complete all of Worksheet 12 on tenure and rights to trees, nor Worksheet 14 on whose rights will be affected, although it may still be useful to investigate intra-household division of rights to trees and tree products.

Deciding which worksheets to use and which to leave out is up to you. However, your decision to exclude any particular worksheet or area of investigation should be carefully considered: a common mistake is to assume that you know things that you have not actually specifically investigated. For example, one of the areas where "common sense" knowledge is often not sufficient is gender analysis: very often, experienced field workers think that they know exactly how tasks, responsibilities and rights are divided between men and women within a household. Through further investigation, however, they usually find that their ideas are based on accepted cultural attitudes, and that the use of the worksheets can contribute significantly to improving their knowledge of this subject.

If a field worker is working with a specific household with an already identified need, the community needs and its worksheets do not have to be considered. The field worker should focus on what factors are relevant to that household and its need.

Should all the worksheets be completed? The purpose of the worksheets is to provide the tools to explore all the topics. However, for most projects and programmes you will not need to use all of them. Different users will need different worksheets, and it will be rare for a user to need to complete all of the questions in a selected worksheet. The answer to the question "What do I need to know?" will differ according to the needs and nature of the community and the objectives of the project. For example, a field worker in a small homogeneous community in a physical environment that has little variation would need to use fewer worksheets in less detail, and a field worker who is attempting to identify more niches for a tree species which is already grown in the community would probably refer to still fewer.

The Case Study in Appendix 1 is typical of the heterogeneous situation found in most projects. Based on the selection of tree species in a project in Asia, it is a joint community-government project: some of the tree species have already been determined by the Forestry Department, but other tree species, as well as the planting locations and spatial arrangement of all the species, remain to be chosen by the community.

It is not important to follow a specific order when collecting the various types of information, though it may be logical to use roughly the order given in this manual. This follows a progression from simpler, more descriptive information of the physical environment, which makes greater use of secondary sources, to more complex and potentially more difficult to obtain information about the socio-economic environment, tree management and tenure and rights. However, the final order selected will also vary for reasons like the time constraints of informants or household members in the village, the weather (for such activities as transects and visits to fields or forests), and other unforeseeable factors.

The manual has three major components: the text, the worksheets and the examples.

The text: The text explains:

The worksheets: Following each section of text which deals with data collection, there is a "Sample Worksheet." Most of the worksheets are very structured with specific questions listed in a specific sequence. Nonetheless, they are not meant to be used as questionnaires, but rather as tools which can guide the field worker in preparing each step in the process of arriving at tree selection. They should also be used as "state of knowledge" checks by the field worker and the community: after some time in a community, the field worker should sit down with community members to go over the worksheets and determine "how much of this do we know?", establishing what information is still needed and how to collect it.

The worksheets were designed to be thorough, and therefore they will usually include questions which are not applicable to the particular community in which you are working. After you have determined what you need to know, delete or change questions or sections of the worksheet that are not appropriate or expand the worksheets by adding questions and sections as needed.

The examples: Appendix 1 presents a case study which is an example of a complete use of the manual methods for a particular tree-planting project.

In addition, for each worksheet there is an example in Appendix 2 that illustrates how it could be used. An analysis of each example is then presented that explains what was learned by the activity.

The manual is organized around the question:

What do we need to know to identify the tree species that would be suitable for the community?

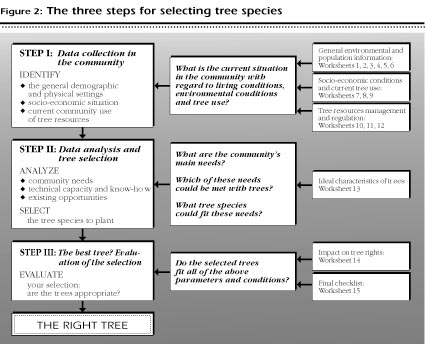

Identifying the appropriate tree is a process which includes three steps (see Figure 2).

General demographic and physical data: Here, basic community information is collected on the following subjects:

Socio-economic conditions and resource use in the community: After the basic information is collected, it is necessary to look more closely at the social and economic organization of the community, which will be important in determining the specific community needs which could be satisfied by trees and tree products. This is done by examining the community production systems, and then selecting a representative sample of community households to develop a household profile which reflects the needs and constraints of the community as a whole. The key information concerns:

Regulation and management of tree resources: The third and final type of information to collect in the community is that which regards resource use and rights to land, trees and tree products. This is the information most specifically tied to the task of selecting tree species to plant and deciding where to plant them. It must be used together with the more general information collected previously [in a) and b) above] in defining both the opportunities and the limitations which will determine the final choices. The three areas to be explored are:

Developing a profile of the community: analysis of the data: Now that all the necessary information has been gathered, it is time to sit down with the community and put the data together into an organized analysis of the community's tree needs, opportunities and constraints. This analysis follows the progressive order used in data collection:

Selecting the most appropriate trees: When the analysis of the needed functions, tree-planting sites, users and rights is done, the moment has come to make concrete proposals of tree species. The checklist of ideal tree characteristics can then be used to match the selected tree as closely as possible to the locations and functions identified.

The impact of the selection on tree and land rights: How would the chosen tree or trees affect existing land and tree tenure systems? Would anyone be excluded from benefitting from the new trees? How would the most vulnerable groups be affected, and what benefits will they derive? These are some of the questions that you will try to answer at this stage of the selection process.

The final check: is it the right tree? The selected tree and planting location are now put through a final exhaustive checklist of questions. These questions cover all of the factors dealt with in this manual as they can be expected to relate to that particular tree. If the tree or locations are found to have significant problems during this check, you must go back to Step 2 (b) above to select another species.

This manual is a tool for enabling field workers to work with the community in choosing the best tree species for its needs. The text describes what information to gather and provides instructions for gathering it, as well as providing guidelines for the analysis and use of the collected data. The worksheets help to structure the process of working with the community to put together the necessary information. The examples help to clarify the way in which the process works in real field situations.

Users of the manual may decide how best to adapt the worksheets to fit their own situation. Although primarily designed for field workers who need to identify appropriate trees species for a tree-planting project, sections of the manual and the worksheets can also be used to obtain specific information for more narrowly defined concerns.