Community Forestry Note 13:

WHAT ABOUT THE WILD ANIMALS? Wild animal species in community forestry in the tropics

by Kent H. Redford, Robert Godshalk and Kiran Asher

Chapter 1: Biogeographical and ecological factors in the use of wild animal species

The goal of community forestry is to meet both short and long-term needs of local people for forestry and forestry-related activities. Until recently, these needs have been viewed as needs for products such as food, fodder and fuelwood. However, increasingly, community foresters are realizing that in addition to this, there is another category of needs which are based not on products in the usual sense of the word but on processes or services. Wildlife plays indispensable roles in the maintenance of complex, healthy ecosystems; as these ecosystems are indispensable to human well-being, the role of wildlife is also indispensable.

Biotic function values of wildlife are those values that result from the ways in which animals interact with the biosphere and the geosphere. These include pollination, nutrient cycling, pest control and many others. The greatest ecological values of wildlife are provided by a largely intact, healthy ecosystem - one that is capable of supporting significant populations of wild animals and particularly large vertebrates. As stated by one author: "The intact ecosystems which harbour wildlife also often provide essential environmental services for surrounding communities, such as a wide range of forest products, water catchment, moderating seasonal flooding, and serving as resource reserves for times of drought or other climatic stress. Local communities often are not aware of the full range of these environmental services nor the direct negative effects that losing them would have on their livelihood" (Kiss, 1990). The same could often be said for the forester-planner, especially as relates to production forestry.

This chapter discusses the different biogeographical and ecological factors affecting animals that must be taken into consideration when developing plans for integrating wild animal species into community forestry projects. In particular, "source faunas" (see below) are examined, including animals' intrinsic genetic and phylogenetic characteristics. The ecology of harvesting and the direct impacts of recent human activity are also discussed.

Source faunas

Different areas have different fauna. Some areas have high species diversity, others low species diversity; some have many large species and few small ones, and some the reverse. Therefore, humans living in different areas have different faunas available to them. The faunas available to a given population are referred to as "source faunas."

The nature of source faunas has tremendous repercussions for the potential patterns of human use of wildlife and whether the incorporation of wildlife into community forestry projects is feasible. Considerations such as whether the animals will attract tourists and will be amenable to sustainable food production programmes or will have market value, necessitate that project planners develop a sound appreciation of the nature of the source fauna in their proposed project areas.

The three tropical regions discussed in this paper (Africa, Latin America and, Asia and the Pacific region) have fundamentally different source faunas. The variation in number and composition of source faunas can be explained by the three basic categories identified by Bourliére (1988): historical, physical and biotic.

Historical factors

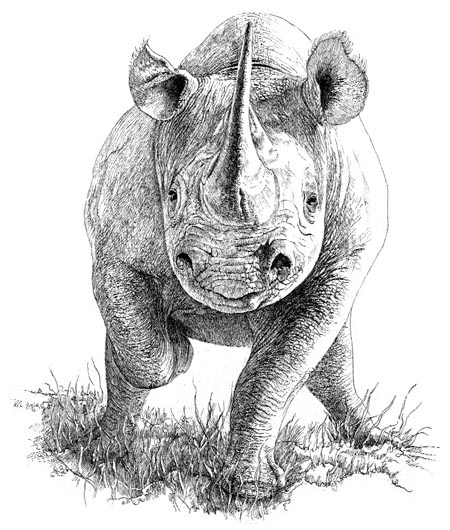

In order to understand the composition, and therefore the human use, of the fauna at a given location, it is important to consider the evolutionary history of an area. The fact that primates are not found in Australia, nor rhinos in South America nor armadillos in Africa, is due to the evolutionary origins of these groups.

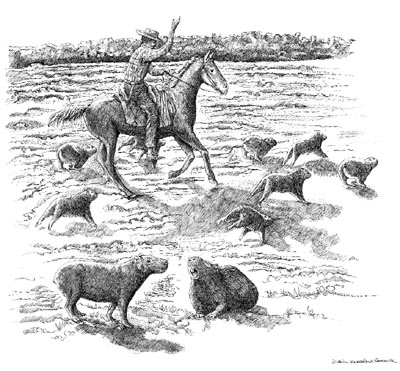

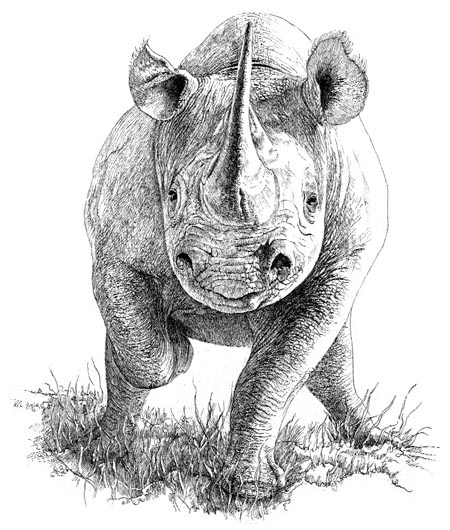

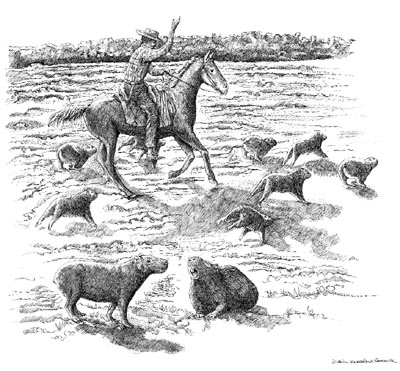

Continental differences are profound. For example, in African savannas, there are about 78 species of bovids - oxen, buffalo, antelope and their relatives (Sinclair, 1983) in addition to the "mega-herbivores" - giraffes, elephants and rhinos. By contrast, in South America, only about seven hoofed animals (ungulates) like the tapir, deer and peccaries occur in tropical savanna formations and there are no animals in the "mega-herbivore" category (Redford and Eisenberg, 1992).

The comparative poverty of species in South America is a geologically recent event. The dramatic difference between the two physiognomically similar savannas of Africa and South America is due to the fact that during the last glacial period, about 11 000 years ago, South America suffered extinction of at least 41 genera of large herbivores including all of its mega-herbivores (Owen-Smith, 1988).

Historical factors also include the phenomenon of dispersal of animals from their areas of origin. Deer provide an example: they did not evolve in South America but were one of the groups to move across the Central American land-bridge. Dispersal factors help to explain the pattern on islands, with continental islands bearing a fauna that is much more representative of the nearby continent than that of oceanic islands.

Physical factors

These include geological constraints such as the size, location and isolation of land masses, as well as the presence of mountain ranges, rivers and other shaping landscape features. For example, the ranges of some tropical mammals do not extend across Africa's Dahomey Gap.

This category also includes climatic parameters. For example, animal species diversity generally decreases with increasing aridity and with increasing altitude.

Biotic factors

This category refers to the ecological mechanisms that mediate the number and abundance of animal species, and therefore their availability for use by humans. It includes the external, environmental influences together with internal, species-specific regulators such as an individual's phylogenetic make-up.

The first of the external, environmental regulators is plant species diversity itself. There seems to be a generally positive correlation between the number of species of plants and the number of animals. This is due not only to the fact that greater numbers of plant species provide greater sources of food, but also because the increased architectural complexity of the forest associated with more diverse vegetation seems to provide the variety of habitat that allows greater animal diversity. Increased environmental heterogeneity increases the number of microhabitats for animals and their prey.

Changing environments and changing patterns in faunal occurrence: The composition of a source fauna is also influenced by site changes and modifications to forest vegetation. It is important to understand some of these potential influences in order to help predict fluctuations in source fauna populations.

Variations in the presence and abundance of animal species within a site may be due to natural succession in the vegetation, to changing patterns of human use, or to a combination of both these factors. For example, when a one hectare patch of forest is cleared by a forest-farmer to plant a garden, the patterns of faunal abundance at this site are changed. The garden's changed biotic and other conditions will cause some species to become more abundant and others to become less abundant or absent. These microhabitat changes also extend into the surrounding forest because the biotic conditions along the forest edge change as well. Typically, the newly made garden will harbour a set of invertebrate species that favours warmer, drier conditions with a preference for the crop plants or the forest weeds that become more common at the site. Research in many parts of the tropics has shown that these changes in vegetation and insect populations are mirrored by changes in the bird, mammal and herpetofauna (reptile) populations.

After the garden is abandoned and as the vegetation structure and plant species compositions change once more, so too do the animal communities. Often, a few of the forest-dwelling species that were rare in the forest become very common in the garden fallow. This is a pattern that has been well documented for rodents (Peterson et al., 1981; Medellin, 1992). In turn, these changes will affect the number of game animals available to a hunter, the nature of the animal-mediated pollination, the number and density of pest species, and many other factors of keen interest to the local humans.

The changing patterns of habitat use by game animals in response to the creation of forest gardens creates the opportunity for what the anthropologist Linares referred to as "garden hunting." Garden hunting describes the tendency of many game animals to be attracted to garden sites where they are killed by humans. In some cases they are attracted to crop plants, in others to the weeds that flourish under increased light and in other cases they may simply be easier to kill in gardens than in the forest.

Fallow gardens are important hunting sites for humans. In some cases the attraction of game animals to the fallow site is consciously encouraged by planting wild species that bear fruit attractive to game animals.

Changes in forest size and connectivity can also change the fauna of a given area. For example, as a forest is fragmented, the fauna loses those species whose area-requirements are now no longer met, often the case for the large predators, large primates and large ungulates. Not only are these species no longer available for direct exploitation by humans, but their absence will change the remaining community of species (Redford, 1992). For example, in small forest patches in eastern Brazil where ocelots are absent, the rodent community is impoverished due to the increased abundance of Didelphis opossums (da Fonseca and Robinson, 1990). The construction of wildlife corridors can partially offset some of these loses.

The severity of the effects of forest fragmentation is dependent upon the scale of change. In the Ituri forest area of Zaire, where second-growth forests are bordered by vast areas of uncut forests, few game species inhabiting the secondary forests are scarce, largely due to the presence of the primary forest (Wilkie and Finn, 1990).

Intensive selective harvesting of forest products can also have implications for patterns of faunal abundance and their use by resident human populations. Johns (1985) reviews the effects of selective logging on tropical forest animal communities and concludes that some animal species are adversely affected, some are entirely unable to survive and others are able to maintain viable populations or to flourish. Of those species most frequently of interest to humans, many are negatively affected by large-scale selective logging.

The harvesting of non-timber forest products can also have effects on the fauna through factors such as the creation of competition between humans and animals for resources like fruit (Redford, 1992).

These factors are not simply matters of academic interest but must be carefully considered as they will influence the outcomes of any attempt to integrate the increased use of wild animal species into other ongoing activities.

Phylogenetic constraints: When assessing the suitability of different species for sustainable human use, intrinsic, species-specific factors must also be considered. These refer to those characteristics of an animal's biology that are primarily determined not by environmental factors but by genetic heritage. Many of these factors can be modified slightly by environmental conditions, though only within genetically determined limits that cannot be surpassed. For example, by changing diet and light regimes, the onset of reproduction and litter size of some animals can be somewhat modified.

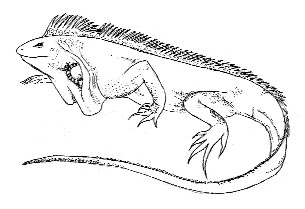

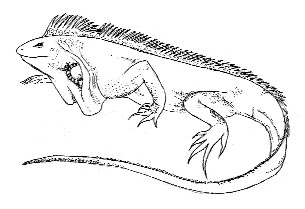

These characteristics are referred to as belonging to the animal's phylogenetic inheritance, and they include such basic traits as homeothermia (the nature of "warm-blooded" animals, such as mammals, which maintain a constant body temperature) and heterothermia ("cold-blooded" animals, such as reptiles, which do not maintain a constant temperature).

A basic understanding of the existence of phylogenetic constraints is essential when evaluating management plans directed at a single species or comparing the potential of two different species. The genetic difference between heterotherms and homeotherms is one of nature's most basic divisions between animals. This difference is related to many basic biological characteristics. For example, homeotherms typically have a small number of young. Each of these few offspring receives both a relatively large prenatal investment and a considerable postnatal investment in care and feeding. This compares with the much greater litter size of heterotherms and the virtual lack of parental investment. The result is that the reproduction of heterotherms is more rapid than that of homeotherms (Peters, 1983).

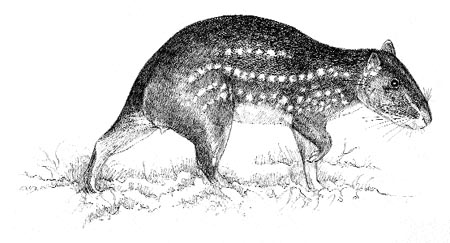

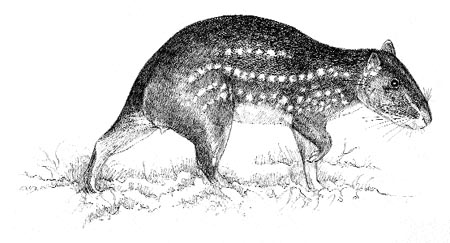

An example illustrates the importance of considering phylogenetic constraints when assessing different wild species for integration into community forestry activities. In West Africa, there has been a great deal of work devoted to the biology of giant forest rats (Cricetinomys) as they would appear to be ideal candidates for sustainable harvesting. These large African rodents belong to the family Cricetidae and can produce 24 young a year, a reproductive rate not uncharacteristic of species in this family. The successful experience with these large rodents has sometimes been used as evidence that similar work should be done with the large rodents of other tropical forests. However, in the Western Hemisphere, the large forest rodents are not cricetines, but belong to various families of Hystricognath rodents. For example, the paca (Agouti paca) can produce only 2.5 young per female per year. The other large rodent of these forests, the agouti (genus Dasyprocta) produces only about 3.0 young per female per year (Eisenberg, n.d.). This dramatic phylogenetic difference between reproductive parameters of different rodent families would be an essential component of any decision to manage these forest animals.

Body size and food habits: An evaluation of the suitability of certain species must address itself not only to its phylogeny (its genetic lineage) but also to another intrinsic, species-specific factor: body size. This factor is related to the food habits of an animal in many ways. Small body size allows exploitation of types of food that are not available to large-bodied animals. Large body size, conversely, allows animals access to more abundant food and to food of a wider range of sizes (Peters, 1983).

The giant pouched rat (Cricetomys gambianus) attains a maximum length of about 75 cm, including its long tail. It is found in Central Africa, from Gambia to Sudan and in South Africa up to the Northern Transvaal. Pouched rats are characterized by cheek pouches in which they carry their food.

Body size is greatly influenced by the difference between heterotherms and homeotherms. Most heterotherms are small (such as reptiles and insects) as compared to homeotherms (mammals and birds). Homeotherms of all sizes produce much less body weight per unit of energy ingested than do heterotherms, primarily because they burn the energy to maintain a constant body temperature and high rates of metabolism (Peters, 1983).

The importance of considering the interaction between body size, food habits and reproductivity is illustrated in an example originally given by Kleiber (1961) and expanded on by Peters (1983). If 10 tons of hay are fed to two half-ton steers and an equal amount to 500 two kilogram rabbits, both will reduce their food resource to 6 tons of manure while producing 0.2 tons of new tissue. In other words, assimilation efficiency and production efficiencies are independent of size. The remaining 3.8 tons will have been used to produce energy that was lost as respiration, in large part to maintain a constant body temperature. The major difference in the two species is that 1 ton of rabbits will eat all their food and produce all their growth in only three months, whereas 1 ton of cattle will require 14 months.

If this type of analysis were extended to insects, 10 tons of hay would support a population of 1 million grasshoppers for nine months, but at the end of that time they would produce 2 tons of new grasshoppers, or 10 times more new tissue than the homeotherms, leaving behind 6 tons of manure and burning off the energy in only 2 tons of the food (Peters, 1983).

In other words, from the perspective of production for human consumption, small heterotherms (insects) may very well be a better investment than large homeotherms with the same food habits (cattle). Though this example involves controlled feeding experiments, the larger point, in terms of maximizing food production, might be that in many circumstances where both types of animals are in common use as food, humans may wish to focus harvesting schemes on invertebrates rather than vertebrates.

Reproductive rates: Another clear concern for the human consumer is the pattern of reproduction of a candidate species. In addition to the factors discussed above, reproduction is also strongly influenced by body size. Larger animals tend to have fewer young than smaller animals. However, the young of larger animals tend to be larger, with the result that the total mass of the litter does not vary much among vertebrates or, perhaps, invertebrates of similar size.

When assessing different candidate species for community forestry projects, the following parameters of reproductive rate must be considered:

- age of first reproduction;

- litter/clutch size;

- size of neonate or egg;

- interbirth/clutch interval; and

- age of last reproduction.

Population density and carrying capacity: A large-bodied animal that produces many offspring might seem to be ideal for the purposes of human exploitation. However, individuals of such a species may not be common: they may occur at a low population density, decreasing their usefulness. The factors that control the density of animals can be divided into two major groups, intrinsic and extrinsic.

Intrinsic factors governing density are closely related to body size and food habits. As a general rule, population densities decline with: 1) increasing body mass (big mammals are less common than small ones); and 2) more specialized food habits (species whose diet allows them access to a greater variety of food resources are more common) (Robinson and Redford, 1986). The relationship of increasing density with decreasing body size is true across a tremendous range of sizes and animal groups. On average, smaller animals are always more abundant than larger ones (Peters, 1983).

The second group of factors governing population density are extrinsic ones, that is, environmental factors which are not phylogenetically based. Extrinsic factors are frequently related to the carrying capacity of a habitat - the ability of a habitat to provide a given species with shelter, food, water, etc. In habitats that contain abundant food or shelter, the density of a species would be greater than in a habitat with less food or shelter. These factors are sometimes modified by local communities.

Many other factors can influence and control density levels of a species such as disease, predators, exceptionally unfavourable weather or fire. Some species, like migratory locusts and adult moths, vary in density depending on season or rainfall.

The indirect effects of loss of fauna

When considering the harvesting of wild species, it is important to understand not only the impact on the target species but also the impact on non-target species. As stated by Naiman (1988): "... although less widespread and ecologically influential than in the past, within our remaining natural systems animals continue to play significant ecological roles that go far beyond their immediate requirements for food or habitat. In many cases they are responsible for bio-geo-chemical, successional, and landscape alterations that may persist for centuries."

Although many ecologists have documented the important roles played by large animals in seed dispersal, seed predation, herbivory, pollination and predation, until recently few have considered what would happen if these animals were removed from the system. There is a growing body of work which suggests that in tropical forest ecosystems, large vertebrates perform very important ecological roles, and that their removal would result in a changed forest. A more holistic approach should include consideration of these factors, which can be referred to as the ecology of harvesting. It is essential to consider it if long-term ecological sustainability is to be the result of community forestry activities. (For more detailed references see Redford, 1992.)

The concentration on large animals is by no means meant to dismiss the role of small animals in structuring ecological communities. Work on termites, earthworms and other insects, to mention a few, has shown the critical role these small species play in such processes as nutrient cycling and decomposition. Yet, the incorporation of large wild species into community forestry programmes has received the most attention for several reasons: 1) because of the obvious vegetation structuring role they play in ecosystems; 2) because they are frequently the major targets of human interest; 3) because there has been more work done on their ecological roles in this habitat; and 4) because the possible ecological effects of their absence are better understood.

Vegetation structure

The importance of large animals in structuring forests has been discussed for deer, tapir and peccary (Dirzo and Miranda, 1990), for rhinos in Nepal (Dinerstein and Wemmer, 1988), and for elephants in the Ivory Coast and in Uganda (Alexandre, 1978; Chapman et al., 1992). In more open vegetation formations of Africa, for example, elephants can transform woodlands into open grassland, accelerating the release of nutrients (Owen-Smith, 1988).

Seed dispersal

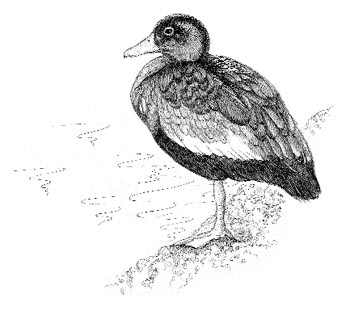

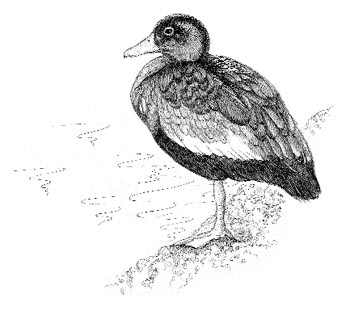

Many authors have documented the important role played by large birds and terrestrial mammals in the dispersal of the seeds of tropical plants. Based on his work in Panama, Howe (1984) stated that "animal-mediated dispersal is certain to be critical for the demographic recruitment of many or most tropical forest species." Large birds, particularly the cracids, hornbills and turaco, are among the most important seed dispersers. Many of the species of cracids, particularly the curassows, are the species whose local populations are most rapidly depleted by hunting. Because of the cracids' importance as seed dispersers and their susceptibility to hunting, Silva and Strahl (1991) have suggested that "human impact on the Cracidae may have irreversible long-term effects on the biology of neotropical forest ecosystems." Similar arguments have been made for other large birds in Africa, Asia and Australia.

The other group of important large seed dispersers are the primates, including chimpanzees, spider monkeys, orangutans and woolly monkeys. Like large birds, large primates are highly prized game animals and are very rapidly hunted out of a forest (cf. Peres, 1990). In the absence of these and other large primates, many species of plants may experience severely altered seed dispersal patterns and at least some trees would become locally extinct.

Predation

The role played by predators in structuring communities has been well studied in marine and intertidal systems. This work has shown that predators can increase the overall species diversity in a community by decreasing the abundance of smaller predators and competing herbivores, and by reducing dominance of prey species. Research of this sort has not been conducted in tropical forests, but biologists working in various locations have observed that the decrease in abundance of large predatory mammals is correlated with the increase in abundance of medium-sized terrestrial mammals. Absence of large predators such as tigers, jaguars, leopards and ocelots also seems to result in dramatic differences in densities of prey species, which are found in more regular numbers in the presence of these predators (cf. Emmons, 1987).

These large animals provide what Terborgh (1988) has referred to as a "stabilizing function." Animals like black caiman, jaguars and harpy eagles maintain the remarkable diversity of tropical forests through "indirect effects," a term referring to "the propagation of perturbations through one or more trophic levels in an ecosystem, so that consequences are felt in organisms that may seem far removed, both ecologically and taxonomically, from the subjects of the perturbation" (Terborgh, 1988).

In many tropical habitats, large animals are no longer present in numbers that even approach their past densities. They may not be completely extirpated, but they are only present in the area in very low densities. Even if elephants, bearded pigs, rhinos, mandrills or jaguars have not gone extinct in the wild, their populations may have been reduced to such an extent that they no longer perform their "ecological functions." In such habitats the animals are, in all probability, ecologically extinct. "Ecological extinction" is defined as "the reduction of a species to such low abundance that although it is still present in the community it no longer interacts significantly with other species."

The animals that are the most popular game species, the ones most heavily affected by human activity and the ones whose populations have most likely become ecologically extinct, include the most important predators and the large seed dispersers and seed predators in tropical forests.

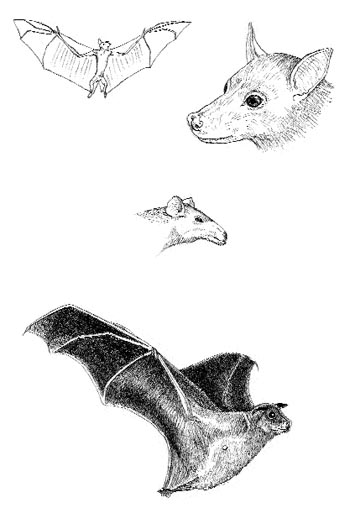

Invertebrate wealth

Invertebrates play a major role in the diets of many tropical people. Entomophagy (the eating of insects) has not received adequate attention by researchers for a number of reasons. Many investigators are concerned with consumption of highly visible, measurable vertebrate prey and dismiss the importance of invertebrate consumption, especially insects. Over 500 species of insects have been recorded worldwide as human food, which includes all major insect orders (DeFoliart, 1990). These are frequently eaten in the field as they are encountered and almost never quantified. These food items are generally overlooked or are merely reported as "grasshoppers" or "locusts" on food item lists, rarely identified to species (DeFoliart, 1989). Sometimes, researcher disgust and bias against entomophagy as a "primitive" practice may cause informants to hide certain food resources (Posey, 1987).

Edible insect food resources are incredibly varied. A study by Ruddle (1973) revealed at least 25 insect species in the diet of the Colombian Yukpa. Dufour (1987) reported 20 species for the Tukanoans of southern Colombia. In southern Zaire, a study restricted to caterpillars found at least 35 species were consumed (Malaisse and Parent, 1980). Mexico has diverse groups that eat insects, and more than 200 species are consumed there (DeFoliart, 1990). Honey is an important food item in many cultures and is collected from both wild and domestic sources. It is frequently consumed together with bee larvae, which provides additional benefits from protein and fat.

Various studies have been undertaken on the nutritional value of insects as a food source. Crude protein may range up to 60 percent or more (dry weight). High energy is derived from the high fat content. Tests were conducted on a termite (Macrotermes subhyalinus) and a palm weevil (Rhynchophorus phoenicis), commonly consumed in Angola. The caloric values were 613 and 561 kcal/1 000 g, respectively, and they also included many important vitamins and minerals. By comparison, corn provides only 320-340 kcal/1 000 g (Oliviera et al., 1976). Comparable results were found for insects consumed in the Amazon (Dufour, 1988). Other invertebrates are also consumed and can be very important locally. The large West African land snails (Achatina spp and Archachatina spp) are eaten widely throughout their range. Protein analyses show their flesh to be similar to beef (Ajayi, 1971). This mollusk may prove to be an important species in low-cost production schemes. Other invertebrates widely consumed include crabs, crayfish, mussels and clams, which pertain to fishery issues. They are mentioned here only as a reminder of their importance in many tropical diets and the need to learn from local communities what range of wildlife enters their food preferences and habits.

Hunting patterns

The most highly sought after species are usually large-bodied prey, generally mammals (Redford, in press). These give the greatest return for time invested in hunting. Mammals are universally sought and most consumed, followed by birds, reptiles and then amphibians. An illustrative figure from Malaysia indicates that 96.8 percent of the game animals caught are mammals (Caldecott, 1988). However, significant numbers of smaller (non-game) animals are also consumed, including large amounts of invertebrates.

These preferences appear to narrow with acculturation and articulation with Western society and cash markets. This trend has been noted anecdotally but rarely quantified. A comparison of forest colonists (in closer contact with the "outside world") and indigenous peoples in South America shows these differences in their hunting patterns. Indigenous peoples hunted mammals, birds (and probably reptiles) at a higher rate and in a wider variety than colonists, with colonists hunting a small subset of the diverse group taken by the indigenous peoples. Some overlaps occurred with certain favoured species commonly hunted by both groups (Redford and Robinson, 1987).

Prey density is very important in determining potential hunting success. In general, smaller species are more common and reliable than larger species. Traditionally, indigenous groups moved as hunting returns and garden production diminished, but most of these groups today are no longer able to relocate. The increasing encroachments on hunting areas used by traditional societies have restricted their freedom of movement. As a result, they become increasingly sedentary. This is often encouraged or imposed by national government policies, social policies of non-government or missionary groups, and development agencies, as well as by changes in land tenure systems. This increased sedentariness leads to intensification of local resource depletion and eventually a dependence on agriculture and domestic stock. New technologies further accelerate this process. These technologies are not confined to manufactured tools. Yost and Kelley (1983) note an example where the recent introduction of dogs among Waorani tribesmen has allowed them to hunt species that were previously ignored or rarely hunted.

Wildlife or domestic stock?

Early European settlers began introducing their livestock almost as soon as they arrived in the tropical lands they colonized. These exotic breeds often proved to be poorly adapted to tropical climates and diseases. Still, because colonists were familiar with these animals, the introductions continued and most local sources of animal protein were ignored. Many development institutions continue this legacy today and fund programmes that promote widespread domestic livestock use. These livestock programmes often occur in inappropriate situations where local wild species might provide more positive results.

Alternative sources should be considered for community development schemes outside the traditional domestic species of chickens, goats, sheep, pigs and cows. Usually, cultural values and preferences for various wild foods are overlooked in development projects.

For example, cattle are strictly grazers that do not exist well on poor quality forage. As range quality goes down, exceedingly high amounts of pasture per head are required, or supplemental feed must be given. Increasing use of grain to fatten meat animals often diverts these foods from the rural poor. Farmland may also be shifted from human food production to crops, such as sorghum, for animal feed. The resultant meat products can be very expensive and are consumed by higher-income urban dwellers. Goats and sheep are superior producers to cattle in marginal environments but when overstocked seriously degrade these habitats.

In many instances, managing a mix of native wildlife species could provide similar production with less damaging effects. Some habitats are very inhospitable to conventional stock, and only wild species, better adapted to restricted plant and water resources, can be used without causing serious environmental degradation.

Wildlife has a number of advantages over domestic species. In addition to high consumer preference for wildlife, dressed carcass weight in wild species is usually a higher percentage of the live weight (Ajayi, 1983). This can mean comparable or less waste than with domestic breeds. Meat from wild species generally has a very high protein content. Native species are well adapted to local climate and disease and can efficiently utilize the native plant cover. Despite these advantages, use of wild species for meat production continues to receive insufficient attention.

The nutritional advantages of wildlife

There is an important consideration that is frequently neglected by those studying the nutritional relevance of animal protein: the regularity of the supply of protein is probably more important than overall average consumption. In other words, eating a small amount of animal protein each day may be better for nutrition than eating a great deal once every 20 days. In this regard, the use of non-domesticated animals, particularly wild animal species, assumes considerable importance for two reasons (Dwyer, 1985).

First, many wild animal species are small, particularly if invertebrates and small fish are included. These animals may be eaten frequently by children: Chavunduka credits insect consumption with preventing many potential cases of kwashiorkor among the young in remote rural areas of Zimbabwe (cited in DeFoliart, 1989). Because small animals are frequently eaten as snack food or caught and prepared away from the main kitchen, their consumption has been vastly underestimated by researchers. These small animals are consumed much more frequently than larger game animals and certainly more frequently than meat from domestic animals. Another example is the peri-urban areas of Zambia and the more densely settled farmlands in other parts of the country where mice, moles, gerbils and termite alates are extensively consumed (Pullan, 1981).

The second reason why meat from wild animals is frequently more important to nutrition than that of domestic species is their lesser market value. Only certain species of wild animals have a market value, while all species of domestic animals have such value. As a result, domestic animals are frequently not consumed by their owners but are reserved to be sold at market when cash is needed.

The result is that both domestic animals and larger game animals are rarely eaten by subsistence farmers or hunters and their families because of their market value. Instead, smaller wild species with little market value, particularly insects, often missed by researchers, may supply a very important source of nutrition.

TOP || TABLE OF CONTENTS || NEXT

Chapter 2: Socio-cultural values of wildlife

Although the main focus of this study is the use of wild animals for food, it is important to examine how wild animal species are valued and how they influence the culture and belief systems of rural societies more generally. Thus the focus of this chapter is on the social, rather than technical or managerial, implications of wildlife in community forestry projects. It reviews the spiritual, symbolic and ceremonial importance of wild animals; examines the significance of wildlife in hunting societies and in indigenous systems of medicine; and considers the impact of gender roles on the use and management of wild fauna.

Studying socio-cultural values is important in two ways to foresters. On the one hand, past attempts to introduce forms of animal use that contradict local cultural or religious beliefs have resulted in failure. Thus, an understanding of these belief systems is vital before instituting development projects that target certain species which may be regarded as inappropriate by the social group involved. On the other hand, animals that are positively valued are quite often of interest to the community, which may wish to reintroduce, protect or manage such species.

Religion, mythology and folklore

Wildlife fills a myriad of roles in the belief systems of human societies. Both archaeological and ethnographic records show that nature, and especially wild animals, are central to the religious practices, mythology and folklore of many societies. As such, it is important to have an understanding of these dimensions in developing a strategy for community forestry and wildlife management.

Common to many societies is the belief that wild animals have superhuman or godlike powers. Early art, including palaeolithic cave painting, shows that the veneration of animals is an ancient form of worship (Marshak, 1972). Numerous early peoples practised religions in which wild animals featured prominently, and this pattern is still observed in many contemporary societies (Diamond, 1987). Several religions practised in Asia, Africa and among Native Americans, have retained the respect for other forms of life as a basic tenet. This idea is central to the ideology of animism, a cosmology found in many areas of the world, which posits that all creatures and objects possess souls (Hitchcock, 1962).

The association of major deities or spiritual beings with animals, in which creatures serve as the assistants, symbols or incarnations of religious figures, is characteristic of some of the world's major religions. The ancient Egyptian pantheon, for example, with its zoomorphic gods and the related remains of mummified animals in the cult of the dead, represents a virtual catalogue of the Nile Valley's fauna. There are parallels in Christian iconography, with early evangelists associated with animal symbols: Mark is represented by the lion, John by the eagle and Luke by the ox. In terms of current observance and imagery, Hinduism provides other pertinent examples of the important role of wild animals in religious practices. Here, all religious ceremonies or auspicious occasions begin with a prayer to the elephant god Ganesh. Wild animals are the mounts or chariot pullers of many Hindu gods and goddesses: Durga or Kali rides a tiger, Murugan rides a peacock, and the great Hindu god of the sky, the raptor Garuda, is believed to have brought the sun down on his wings.

Another belief in the spiritual relationship between humans and animals is that of the guardian-spirit animal. The creature may be a bird, a mammal or even an insect. In the various Native American and Asian societies where this belief is held, humans develop a special bond with a wild animal through a dream or vision in which the animal's spirit communicates with them. The spirit may endow the person with extraordinary powers, prayers or paraphernalia, which can then be drawn on in times of need or crisis.

Some American Indian and Aboriginal Australian shamans are also noted for their ability to tame as well as communicate with wild animals. This special attribute has likewise been associated with Buddha, Saint Francis, the prophet Daniel and other holy figures from larger societies. The taming of wildlife for spiritual purposes may have also played an early role in the process of animal domestication (Zeuner, 1963; Savishinsky, 1983; Tuan, 1984; Budiansky, 1991).

A different form of guardianship is expressed in beliefs that place animal spirits in the role of protecting wildlife against human abuse. For example, Hitchcock (1962) describes the role of the tabanid fly in regulating the fishing of the Montagnais of eastern Canada. The fly is considered overlord of salmon and cod, and hovers over the fishermen whenever the fish are taken from the river "in order to see how his subjects are being treated." Occasionally, the fly will bite the fisher as a punishment for wastefulness; the bitten man would expect poor fishing for a time as a further chastisement. Guardian animals may also punish those who disturb a forest or other ecosystem unnecessarily. Certain communities in the Peruvian Amazon fear and respect an "animal-demon" called shapshico, who shoots a tiny dart causing illness and hysteria "if you cut down a tree in his [rainforest] garden" (Kamppinen, 1988).

Another manifestation of the spiritual relationship with the animal world is the totem, a hereditary emblem-animal for a person, tribe or clan, which often gives the person or group its name. Taboos against eating one's totem animal are nearly ubiquitous among groups that have totems. Similarly, many societies forbid their people from eating a certain animal honoured for the legendary assistance it gave to the group's ancestors (de Vos, 1977). In totemic societies, relations to wild species are central to a sense of group identity and solidarity.

Taboos on the use of animals

The various symbolic and religious roles of wildlife exist side by side with the practical uses of animals. Practical uses in turn are determined by certain cultural beliefs, which were originally derived from accumulated collective experience. Certain foods, for example, are "taboo" or forbidden in specific societies. Taboos are the social restrictions placed by a group on the consumption or use of certain species. Central Inuit groups, such as the Netsilik of Canada, Alaska and Greenland, strictly segregate the eating of sea and land mammals, and the sewing of the skins, into the different seasons of the year (Balikci, 1970). The best described food taboos are those of Islam and Judaism, which prohibit the consumption of a range of domesticated and non-domesticated species. These restrictions affect the behaviour of millions of practising Muslims and Jews throughout the world.

The significance of food prohibitions on wild and domestic animals has been the subject of various interpretations. Two main schools of thought have developed in recent years, one with a functional or materialist emphasis, the other with an emphasis on meaning and symbolism (Shanklin, 1985). The former school stresses the functional importance of these animal food taboos, that is, their utility for furthering people's material needs (Harris, 1975). Harris, for instance, argues that historically it made economic and ecological sense for Middle Eastern people to prohibit pigs because these animals were physiologically ill-adapted to the region's climate. People there were better off finding a way to resist the temptation to consume pork, he argues, and so the creation of the taboo on pigs allowed them instead to invest their energy and resources raising more suitable and productive animals.

The second school (symbolic interpretation) has emphasized, in contrast, the role of food taboos in maintaining the integrity of cultural categories and systems of meaning (Douglas, 1970). Douglas has argued that all people divide up the world and its contents, including its animals, into mutually exclusive categories. Such classifications lend coherence and system to the way members of a society order their experience.

These material and symbolic approaches thus indicate widely divergent interpretations of people's behaviour towards animals, though both schools agree that individuals are often not conscious of the "true" reasons behind their conduct. Indeed, as both Harris and Douglas note, followers of a cultural tradition often seize on secondary rationalizations, such as health concerns, to explain their tabooed beliefs and behaviours.

Gender-specific restrictions or taboos on animals form another common pattern. Among the Pedi of South Africa, 12 of the 37 species of wild mammals found in the area can only be eaten by men or boys (de Vos, 1977). Sometimes certain animals, such as rodents, are thought to be "impure" and are avoided, especially by pregnant or menstruating women or by girls at puberty. For this reason, women from some groups in Senegal do not eat bush rats during pregnancy. Among the Evodoula of Cameroon, pregnant women do not consume palm squirrels. The taboos imposed by some sub-Arctic peoples, forbidding women or dogs to eat the bones and flesh of certain animals, are viewed by them as an act of respect for those animals' spirits (Henriksen, 1973; Tanner, 1979).

Age as well as gender figures in some societies' wild animal consumption patterns. In parts of Zimbabwe, certain rodents are consumed by adults but not by children (de Vos, 1977). The Tsembaga Maring of New Guinea place various restrictions on the wild animals that men and adolescent boys can eat but impose no such taboos on mothers and children, effectively channelling most wild animal protein to the people who have less access to domestic meat (Rappaport, 1968). Among various communities in Zaire, a large number of species cannot be eaten by children and women, while some animals are reserved for older men (Pagezy, 1988).

There can also be some rather complex systems of taboos among peoples whose main food source is wildlife. For example, there may be guilds of hunters that specialize in certain types of prey or are subject to particular kinds of restrictions. In the case of the Valley Bisa of Zambia, the hunter's ability to placate the spirits of the game animals can determine which animals he is allowed to capture (Marks, 1984). The Sabuna of Brazil have very complicated systems in which people's age, sex and even number of children influence what kinds of animals they are allowed to consume (Taylor, 1981). Other taboos affect only the behaviour of specific individuals. For example, among the Etolo of New Guinea, a successful hunter cannot eat the animal he kills (Dwyer, 1974). The Hare of northern Canada require a successful moose hunter to give the slain animal to someone else in order to avoid incurring the envy of others (Savishinsky, 1994). Among the Cashinahua of Amazonia, individuals may choose to classify animals as edible or inedible for highly idiosyncratic reasons, such as a personal encounter with an animal in a supernatural experience (Kensinger, 1981).

Project planners and managers need to examine carefully all taboos and related beliefs, and to avoid making assumptions that ignore cultural variation within an area. To assume that one group's taboo on a particular type of fauna is shared by neighbouring peoples, or even among members of the same family, may cause community forestry planners to shun species of wild animals that might otherwise be excellent candidates for development projects. This point is particularly relevant when outside influences have combined to make previously forbidden foods acceptable, as with deer in the tropics (Redford and Robinson, 1987) or when previously acceptable foods have been discarded, as with mice and rats among the Maraca of Colombia (Ruddle, 1970).

Ceremonial uses of wild animals

Tradition not only prohibits the consumption of some animals, it also defines situations in which the use of certain animals is necessary or even indispensable. At a birth, death, marriage, coming-of-age ceremony or other highly significant moments in the social life of a community, the flesh, blood, skin, teeth, bones or other parts of animals may be required for the correct fulfilment of a ritual. Groups in China, as well as Native American groups, for instance, utilized deer scapulae in important divination rituals to guide various activities (Moore, 1957). The animals or body parts used in such ceremonies may be collected by family members, or bought or traded. For example, distribution of game at the time of a girl's first menstruation is vital among the Etolo of New Guinea (Dwyer, 1974) while sloths, not normally hunted otherwise, are essential for the "ceremony of the singing souls" among the Matses of Colombia (Romanoff, 1983).

Various African and Native American peoples celebrate, as a rite of passage, the first slaying of a large animal by a young man (Tanner, 1979). The most important ritual among the Naskapi of eastern Canada, mokoshan, focuses on the communal sharing of caribou marrow and meat, which emphasizes and renews the special relationship between hunters and the caribou's spirit (Henriksen, 1973). The indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest Coast hold a First Salmon ceremony to honour "the first catch from each important stream or area" (Drucker, 1963). Some tribes in this region offer the First Salmon to a sacred eagle to show it respect and to ensure prosperous fishing in the future.

The cultural significance of hunting

Hunting is fundamental to many cultures. The place of hunting contributes significantly to a community's self-definition, a phenomenon noted by anthropologists since the pioneering work of Franz Boaz among the Chinuk over a century ago. The social role of hunting as a cohesive agent, especially among men but also between men and women (see section on "gender factors" below), may be of equal or greater importance than the actual food returned to the village. The process of distributing game can be essential to maintaining social cohesion through its affirmation of kinship and friendship bonds (Stearman, 1992).

Successful hunters accrue prestige. Several indigenous groups in the Beni region of Bolivia (Stearman, 1992) choose to describe themselves as hunters even though hunted game is not their most important source of food. A similar situation is found among the Dayak of Borneo (Caldecott, 1988).

A number of indigenous northern communities continue to combine hunting with another long-established use of wildlife: fur trapping. Recognition of this pursuit is especially important to a comprehensive assessment of the world's forest resources because many of the most valuable northern animals are native both to the boreal forest and to the transitional taiga-tundra ecozone, which together constitute one of the planet's most extensive forested regions. Economically valuable species, frequently hunted for their fur pelts, include varieties of fox, beaver, muskrat, ermine, lynx, mink and marten.

Medicinal uses of wildlife

Another important socio-cultural category is the use of animals or their products in traditional medicines. The vast realm of Chinese traditional medicine (compiled during the Ming Dynasty in a massive 168-volume encyclopedia) provides some examples: meloid beetles taken internally affect the kidneys; boiled cicada skins can calm migraine headaches and other pains; and mantid broth is given to bed-wetting children (Kritsky, 1987).

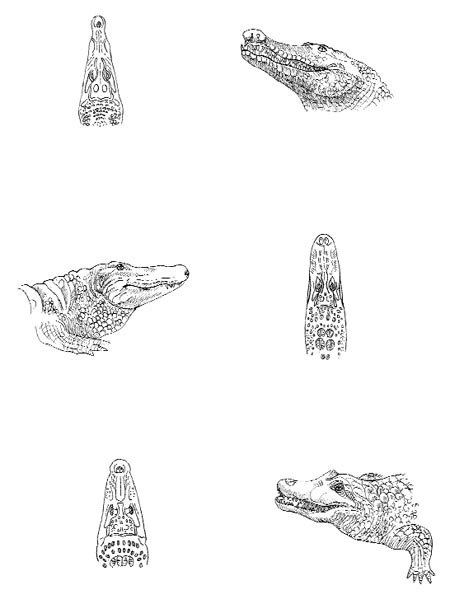

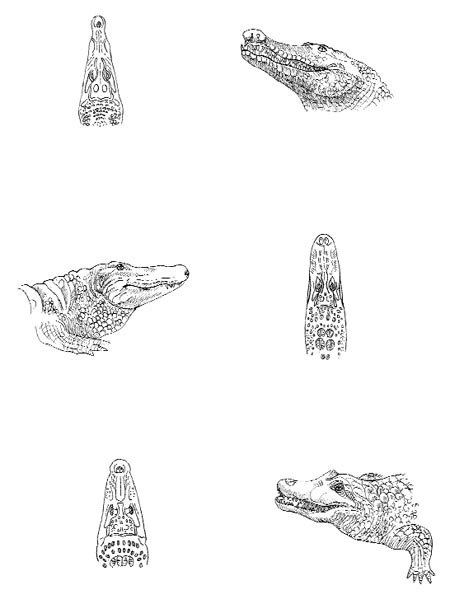

Traditional trading in medicines employing wildlife is still practised on many different levels, from local markets to commercial networks of great magnitude. Interestingly, many similar uses are common to widely separated groups. Oils from crocodiles are traditionally used in treatments of respiratory ailments in regions of Africa (Nichol, 1987) as well as Latin America. Preparations of dried poisonous snakes are administered for eye problems in both Latin America and Southeast Asia.

Thus, widespread medicinal applications exist for a variety of animal products, and a great deal more research remains to be done to explore and assess their physiological effectiveness. The potential value of such work for local people and other populations is suggested, in the case of medicinal plants, by recent and often spectacular finds in the better-developed field of ethnobotany. Applied research of this kind with wildlife could support efforts to maintain both the planet's biodiversity and the diversity of indigenous systems of knowledge and economics (Linden, 1991).

Gender factors: effects on traditional and potential wildlife use

Gender is an important consideration in all development and conservation work. While a lot is known about the nature and extent of gender roles with respect to agricultural and forestry planning, participation and decision-making, much less is known about the gender roles of local peoples with respect to management of wild animal species.

The traditional gender division of labour identifies women as child bearers, responsible for nurturing and healing within household and in the community as well. In order to fulfil this socially defined function, women have a special dependence, which often differs from that of men, on the natural resources around them that they use and often manage (Hoskins, 1980). Thus beyond their accepted traditional roles, women are also often the invisible managers and decision-makers within both the private sphere of the household and the public sphere of the community.

To ensure that both women and men are active participants in and beneficiaries of local community forestry efforts, it is imperative to consider them as equal partners from the outset. This becomes especially important when considering the incorporation of wild animal species into specific projects or activities. For example, in light of the food taboos examined earlier, one needs to ask whether the animals incorporated in the project will be beneficial to women or not. Will the animals be competing for the same resources used by men and women in the area of a project? Will they menace the home gardens for which the women have responsibility?

Project planners need to be aware of the various different and complementary tasks performed by women and men. In particular, adding one more chore to women's already heavy workloads could result in the failure of the project if there is no one to perform the added duties that women were unable to perform. As Hoskins (1980) and others suggest, it is important to consider the role of women and men in planning, participating and benefiting from forestry activities. Hoskins illustrates this point with an example of Kenya beekeepers: it was found that a bee-keeping project in that country was receiving no support from women, until the project director realized that it was culturally unacceptable for women to climb trees and so they were not able to reach the hives. Once hives were placed close to the ground, the women became willing participants.

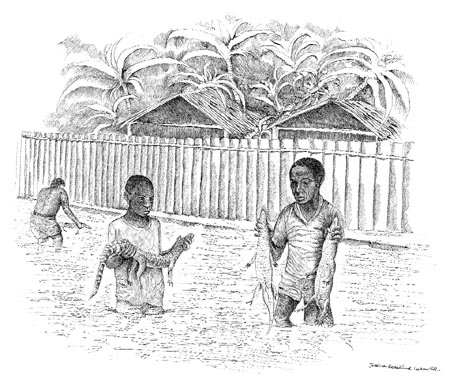

Women and men in rural societies interact with wildlife in other important ways. Studies of traditional gender roles with respect to forest utilization have yielded information on women as gatherers of forest products (usually non-animal products or small animals such as insects) and on men as the hunters of the larger wild animal species. Although men are the primary hunters of large game, women are frequently involved in the catching, butchering and transporting of animals, as well as in the cooking and preservation of their meat. In indigenous communities in sub-Arctic Canada, for example, it is usually women who snare or trap small animals, such as rabbits, for food and fur; it is they who clean, dry and smoke meat and fish; and it is they who scrape, clean and tan hides for clothing and rawhide (Helm, 1981). In Zambia, although women rarely joined men in actual elephant hunts, they performed many vital activities as part of the overall elephant exploitation process.

In other cases, women are the primary procurers of certain animals, despite being restricted to particular technologies. In many indigenous groups in Latin America, for example, fishing with bows and arrows, harpoons and hooks is the responsibility of men, but the use of nets, basket traps and poison fishing is frequently assigned to women and children. Women also identify and track animals in some societies, though this is another important and often overlooked female activity (Hunter et al., 1990). In Nepal men always control the cast nets whereas women catch the same species in wiers.

Women's vital role in stabilizing local economies through flexible and adaptable marketing activities can also be greatly enhanced through access to wildlife as one more option in times of food scarcity.

Effects of market involvement

The effects of market involvement on local wildlife populations and the humans who depend on them are varied and complex. The trade of wild animals generates income and employment, for example, and it has the potential to help manage and regulate herd size and wildlife populations. These are useful by-products of wildlife marketing. On the other hand, poor management and overharvesting are two typical examples of the problems that can be exacerbated by market forces in wildlife trade. While a thorough analysis is beyond the scope of this study, it is important to mention some of the problems, as well as the opportunities and incentives, created by market involvement in order to find ways in which community forestry activities could maximize the positive aspects and minimize the negative impact of this involvement.

Market effects on subsistence hunters

Subsistence hunters, like most other subsistence producers, are being drawn into the market economy, integrating into their livelihoods many consumer goods that can only be obtained with cash or cash substitutes (barter). They enter into a system based on manufactured items, and they swap their game yields for trade goods. Active local markets develop with the growth of rural populations, and the wild animals sold by the hunters become consumer goods for urban populations as well. Non-hunters consume a broad range of wildlife products, most important of which are wild animal meats, which they often prefer to livestock meats. Some types of wild animals are also commodities in international markets, such as those that supply fur, or those in demand as pets or collectors' items (such as butterflies). The combined local, urban and international demands produce market pressures that can - in cases of localized, poor management of harvesting - accelerate the problem of wildlife depletion.

One situation in which this can occur is when hunting groups, in pursuit of trade items, become involved in raising cash crops or domestic animals to provide easily marketed goods. This leads to dramatic changes in lifestyles as these groups become more sedentary to spend time tending crops. Localized game depletion resulting from overhunting can become acute as previously nomadic or wide-ranging hunters change location less frequently but continue to hunt.

A different reaction to market involvement, which is less likely to produce problems of species depletion, is the evolution of cooperative arrangements between certain hunting groups and settled farming populations, allowing the hunters to rely on game meat to provide their trade needs. For example, the nomadic Mbuti of Zaire have developed an interdependent relationship with local swidden agriculturalists in which the Mbuti provide meat and other forest products in exchange for tobacco, iron implements and cultivated crops (Hart, 1978).

In a similar system, Agta hunters in the Philippines trade fish and game with Palanan farmers for carbohydrate foods. Up to half of the meat procured by hunter groups is traded for domestic cereals, while the farmers depend on the Agta for meat and fish. Hunting also provides a protective service to the farms, since deer and wild pigs damage fields (Rai, 1990).

Transactions in which cash is used generally increase with time, particularly as meat traders become involved in the bushmeat market and buying for the local urban markets. Again, in the case of the Mbuti, traders who used to exchange rice or cassava flour for game meat increasingly use money as payment, to the advantage of both hunters and traders. Traders obtain less complicated transactions and credit repayments, and the Mbuti are able to save money for the future and transport it easily (Hart, 1978).

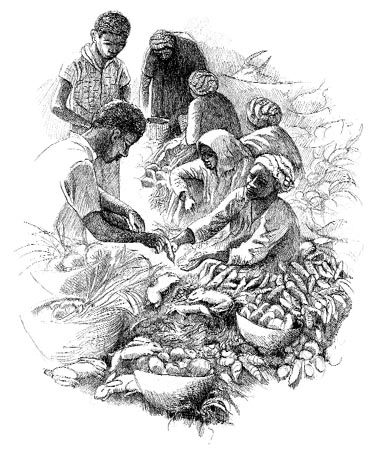

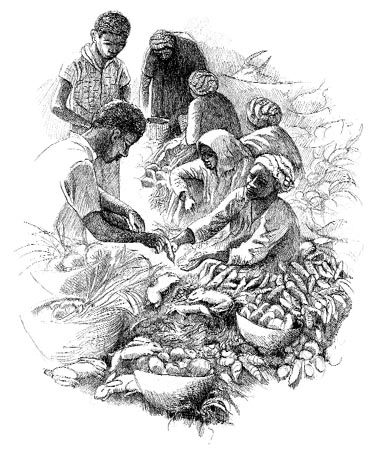

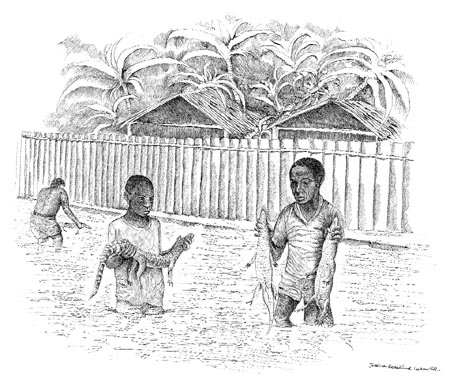

At a roadside market in Ghana, hares, giant pouched rats and cane rats are traded or sold.

The profits of cash transactions are used to purchase perceived "necessities" such as manufactured goods, sugar, coffee, or alcohol, or a high prestige item such as tinned meat. One case illustrative of the irony in some of these situations, described by Mandujano and Rico-Gray (1991), is that of some Maya hunters in Mexico who hunt white-tailed deer to sell the meat, primarily due to "the lack of enough money to buy pork."

In general, wildlife marketing helps to fuel the local economy and raise the incomes and living standards of subsistence hunters and rural communities. Hunters generally find ready markets, driven by urban demand. Wild animal products have great value compared to most agricultural goods and are more easily sold, and thus they are worth transporting over long distances. Hunting is not only the domain of traditional or subsistence hunters: settled farmers also very often hunt and sell game for supplemental income. Several levels of middlemen, processors and transporters are also involved in the wildlife marketing chain. Hence where wildlife meat markets are firmly established, the production and sales provide work and income for a large group of people.

It is important to recognize, however, that market hunting has often had detrimental consequences on local wildlife populations, primarily because this type of hunting can cause the harvest of certain animals at unsustainable levels. This problem needs to be addressed through the development of sustainable wildlife management systems, and community forestry activities can play an important role in this area.

Besides the problem of species depletion, the sale of wild meat often carries other less evident costs. Where incentives to generate cash are powerful, the nutritional status of hunter communities may be compromised by the sale of needed game meat for the purchase of non-edible goods or low-protein foods.

A more subtle effect of market pressure to sell hunted game is the disruption of mechanisms important to social cohesion in some traditional societies, such as sharing hunted meat through established rules which are not applied to the distribution of purchased food (Saffirio and Hames, 1983). In the case of the Mbuti, it is monetization that has produced some social problems, since the members of this group, who generally share all material possessions, do not share money (Hart, 1978). This has the effect of further impoverishing those who are poor. Market hunting may also induce the killing of tabooed species. Taboos are elements of social cohesion and regulation, and strong external pressures (such as market pressures) to go against the established order and break taboos are detrimental to the social harmony of hunter communities.

Urban demand

Urban populations in developing nations have shown rapid rates of increase over the last few decades. In addition to high birthrates, a major factor in this expansion has been migration from rural areas. This recent transition from rural life partly accounts for the fact that urban consumption of wild animal products in developing countries usually far exceeds that in industrialized countries, where city dwellers consume wildlife products less frequently. The newly urban population, which has been recently removed from a rural setting, often retains a preference for forest products, including wild meat, which it is no longer in a position to obtain for itself. Urban demand in these cases can quickly grow to levels that outstrip the ability of the surrounding environment to maintain the desired species, and alternative harvesting and management methods need to be developed to avoid provoking the extinction of these species.

Estimating the extent of trade in wildlife meat

Studies conducted in Africa have shown that the sale of bushmeat in some cities is very significant, and numerous species can be obtained freely in the markets. The meat is often preserved by smoking, allowing it to be transported long distances for sale at far-away markets. These studies show a general trend towards price increase over time in the region, reflecting increased demand and dwindling supplies (Falconer, 1990). Urban-driven trade in these products in Asia and Latin America is also high.

However, estimating total wildlife trade is very difficult and few comprehensive studies have been undertaken. Most small species require no permits, hunting them is not controlled by government authorities, and consumption is not tallied by statisticians. Market surveys are often used to gauge the intake of large populations and to record the species consumed, but the resulting data, which tallies only the species sold, can be biased and lead to incomplete conclusions.

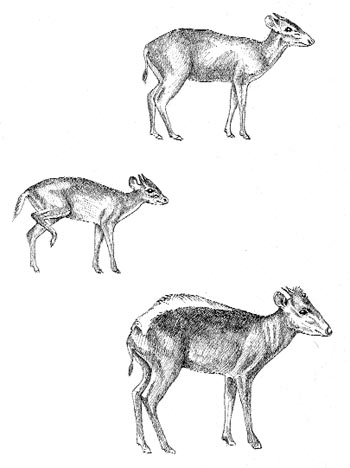

For example, thorough surveys in Zaire by Colyn et al. (1987) have shown that 77.5 percent of all the duikers (mammals the size of small pigs, highly prized for their meat) captured reach the market for sale, while only 13.7 percent of the miscellaneous small game is sold at the public markets. The majority of this other game remains within the community, traded or exchanged locally or consumed within the household, and this generally remains unreported. Thus, in this case, a survey of market sales would not reflect trade patterns on a broader scale. Market surveys may indicate numbers of animals disproportionate to their actual presence in trade.

In spite of the limitations of such data collection, it can be used conservatively to illustrate the magnitude of trade. For example, a study of a single market in Accra, Ghana, traced the sale of 157 809 kg of bushmeat from 13 species in 17 months. This was valued at an estimated US$ 159 976, and the study did not include all transactions at that market (Aisbey, 1974). Data from 15 years (1970-85) of transactions at another market in Accra, the Kantamanto market, showed an average annual sale of 71 000 kg of bushmeat, representing 14 400 animals (Falconer, 1990).

International markets

Market incentives working on an international scale can also be very powerful at the local level. These markets are usually for non-meat products, such as furs, and they can rise and fall quite dramatically with the whims of fashion or the health of far-away economies. Various luxury and medicinal products are also highly valued on international markets. If given a high market value, species may be taken solely for various body parts. Hunting of many of these species is illegal under both national and international laws, but the extremely high value of certain products makes bans on hunting and trading them very difficult to enforce.

Rhinoceros, for example, are usually killed only for their horn. Horn from Asian rhinos, used in various medicinal preparations in East Asia, was reported in 1985 to be selling for as much as US$ 4 090 per pound (Fitzgerald, 1989). Elephants are killed mainly for the ivory in their tusks, and musk deer for the tiny amount of musk produced by the males. High value encourages poaching and continued hunting of these species despite diminished populations. This trend has been seen repeatedly on a large scale with certain valuable species such as crocodiles, elephants and the spotted felines (leopards, etc.), although international controls do appear to be having some limited effect in recent years.

The international pet trade is also very active, and quite lucrative. Bird fanciers pay very high prices for species of the parrot family (Psittacidae). Some individual birds sell for US$ 10 000 or more, and this fuels a large and partly illegal market. Up to 500 000 parrots may be traded annually on the world market, the majority being caught in the wild. In spite of significant levels of illegal capture and sales, the legal trade also operates lucratively: 312 467 parrots were imported legally to the United States in 1985, with retail sales valued at US$ 300 million (Fitzgerald, 1989). Similarly, international trade in tropical insects (mainly butterflies) for collectors is both active and lucrative.

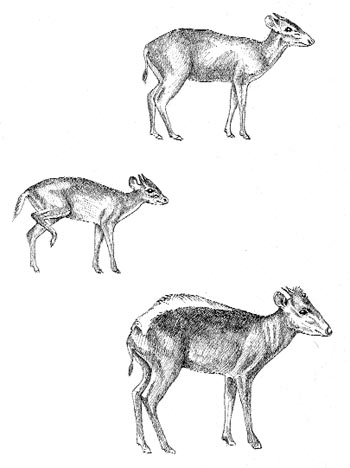

Black-fronted duiker

(Cephalophus nigrifrons) |

|

Blue duiker

(Cephalophus monticola) |

Yellow-backed duiker

(Cephalophus sylvicultor) |

Community forestry and wildlife markets

Many opportunities exist for community forestry to take advantage of existing legal national and international markets, and also for it to contribute to the regulation and rationalization of market hunting. Integrating hunting or raising of wildlife for meat into community forestry projects as an income generating activity is both feasible and advantageous. Supporting and encouraging community integration into marketing systems through training, marketing information systems, infrastructure development, or development of product processing and preservation techniques are some of the ways in which community forestry projects can promote income generation through wildlife markets.

The particular role of community forestry in the development of these activities would be to find ways to support wildlife management for sustainable harvesting to supply market demand. Sustainable resource management systems are badly needed in the area of wildlife for the marketing of meat. Community-based natural resource management, central to community forestry, is likely to be the best approach for wildlife management. This should ideally be combined with government policies to help local communities control harvesting (setting limits on extraction for specific species), encourage good management and, where appropriate, assert other controls over the market. Government assistance can also be used for relocation and restocking programmes to replenish supply in depleted areas.

Market hunting or animal raising for high value wildlife products sought by international markets can also be advantageously integrated into community forestry programmes. With appropriate management, many species of high value animals could be produced in community projects for international distribution. The parrots above are one example and fur animals are another. A highly successful community programme in Papua New Guinea supplies a variety of insects (mostly rare and beautiful butterflies) to collectors worldwide, providing an excellent example of a low-cost/high yield system (Hutton, 1985). This is also true for the live ornamental fish trade, with an annual world wholesale market valued at US$ 600 million, of which increasing quantities are bred in captivity (Fitzgerald, 1989).

It is evident that there is a great market demand for wildlife products, and effective management systems, as well as captive propagation programmes, are unquestionably needed. Market incentives clearly affect the course and magnitude of wildlife use in the tropics. The demand for game meat is significant in numerous countries and overhunting has caused many prized species to decline in numbers. The meat and various other products are highly regarded, widely consumed and usually bring high prices. International regulations, recent national wildlife protection laws and dwindling wild populations reinforce the need for controlled management and production. When integrated into community forestry programmes, the hunting, raising and harvesting of wildlife species could be one type of renewable resource management that would provide benefits to the community equal to or greater than other income generating activities, while at the same time providing important benefits at the level of national and international conservation efforts.

TOP || TABLE OF CONTENTS || NEXT

Chapter 3: Property regimes and wildlife use

Historically, forest-based communities have generally followed communal property rules, with regard both to the land they lived on and to the wild animal resources they used. The customs and institutions that developed around common property regimes usually proved to be viable over the long term from ecological, economic and social standpoints, and they reflected the needs of the local people. Under the effect of rapidly spreading "modernization" over the past few decades, these traditional rules regarding tenure and natural resource use have undergone considerable change in most regions of the world, often losing much of their responsiveness to address overuse and social rules of distribution. In spite of these significant changes, however, contemporary community forestry, concerned with preserving the diversity of the natural environment while improving the welfare of local communities, still needs to consider the relevance of the various traditional forms of property management, particularly to productive and sustainable wildlife use.

Wildlife use and wildlife management

When considering the problems of ensuring the sustainable use of both forests and wildlife, it is important to make a distinction between the use of wildlife and the management of wildlife. "Management" in this context has to do with how species are controlled or directed as a resource, while "use" refers to the functions these species serve or the uses to which they are put. The distinction between "use" and "management" of wild animal species is critical when assessing their integration into community forestry activities. For community forestry to incorporate wild animals, provision must be made for their management, not merely their use.

Relatively little is known about the rules that govern the ownership and use of wildlife in local communities. These rules and the corresponding property regimes in local communities are important factors because ownership will determine who is allowed access and who actually benefits from an enterprise. People will not willingly participate in activities whose benefits do not accrue to them. Ostrom (1990) suggests that in order to apply management principles, it is important to make a distinction between a resource system and the flow of resource units produced by the system. Resource systems are "stock variables," capable of producing a certain maximum quantity of a flow variable without harming the resource system itself. Examples might be fishing grounds, irrigation canals, pastures, or communal forests and the wildlife they contain. Resource units, on the other hand, are what is taken from such a resource system: the fish from the fishing grounds, the water from the irrigation canal, the fodder consumed by animals in a community pasture or the wildlife from a communal forest.

This model helps clarify the two keys for sustainable management: the protection of the system, that is, of the lands, resources and ecological conditions relevant to the system's sustained productivity; and the maintenance of the flow of products, profits and benefits taken from the resource system. Both must be carefully and continually monitored to ensure that sustainability is achieved. In a renewable resource system (such as a forest) long-term sustainability may be assured if the rate of withdrawal of resources, including wildlife, does not exceed the rate of replenishment.

Traditional use, where regulated by custom and taboo, is often geared to the sustainable, long-term management of wildlife resources. These traditional customs, however, have been partially or completely abandoned by local communities as populations have adapted to such new conditions as changes in tenure regimes, incentives provided by markets and pressure from increased population densities. It is now common to see both damaged habitat and "wildlife overuse," that is, use without regard to long-term sustainability, resulting in serious negative consequences to local resource systems.

Categories of property regimes

The traditional use and management of wildlife has been regulated by a variety of property regimes. Property is the basic institution by which individuals, communities and other actors are entitled to the benefits derived from a given resource and by which they may deny these benefits to others (Bromley, 1986). Conventionally, other than individual ownership, three distinct types of property rights are recognized: common, state and open access.

Common property

Many community forestry activities occur within the context of common property regimes, where ownership is communal and access is determined by the larger community. A common property regime can include indigenous reserves, properties owned and managed by a rural community or any resource for which management authority is invested in a group rather than in separate individuals. The rules and regulations governing the use of common property have both spatial and temporal components. Differential access to resources pertains to different community members at different times, depending on what part of the communal managed lands they occupy, what crops or animals they raise, the amount of water to which they have access and numerous other considerations. In a common property regime, local populations clearly define the individuals or households that have the right to use the resource units from the community forest. Such access may be limited by sex, age or other socially defined factors, including restricted use except by special individuals such as shamans or curers. In addition, local user groups may negotiate the rules that regulate the time, place, technology used and quantity of resource units in a particular setting.

Among the small-scale, tradition-oriented communities common in the tropics, access to wildlife is very rarely private property, falling instead under common property regimes, at least in part because most wild animals are fairly mobile. Even when a group claims access to game in specific forest areas and denies hunting rights to others, access to the wildlife for their members is very often communal and not considered private property. Different norms and regimes for using forest resources are followed under different situations.

In most parts of Papua New Guinea, for example, the people are the traditional legal owners of land and wildlife. Among the Maring hunters of the highlands, clan clusters are the units that have rights to the wildlife resources in an area; members of other local groups have no rights over these resources except under special circumstances. Travellers may shoot game of little value if they do so along defined travel paths. Anyone from another clan found straying from paths is considered a poacher (Healey, 1990).